|

This partial manuscript copy is provided as a courtesy. Anyone who wishes a copy may access it from http://www.hatrack.com; therefore we ask that no copies, physical or electronic, be given or lent. Any offering of this portion of the manuscript for sale is expressly prohibited.

This partial manuscript copy is provided as a courtesy. Anyone who wishes a copy may access it from http://www.hatrack.com; therefore we ask that no copies, physical or electronic, be given or lent. Any offering of this portion of the manuscript for sale is expressly prohibited.

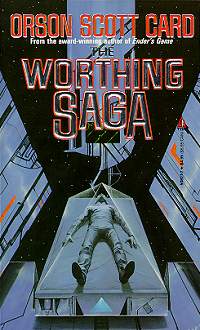

The Worthing Saga

Chapter One

The Day of Pain

In many places in the Peopled Worlds, the pain came suddenly in the midst of the

day's labor. It was as if an ancient and comfortable presence left them, one that they had

never noticed until it was gone, and no one knew what to make of it at first, though all knew

at once that something had changed deep at the heart of the world. No one saw the brief flare

in the star named Argos; it would be years before astronomers would connect the Day of Pain

with the End of Worthing. And by then the change was done, the worlds were broken, and

the golden age was over.

In Lared's village, the change came while they slept. That night there were no

shepherds in their dreams. Lared's little sister, Sala, awoke screaming in terror that Grandma

was dead, Grandma is dead!

Lared sat up in his truckle bed, trying to dispel his own dreams, for in them he had

seen his father carry Grandma to the grave -- but that had been long ago, hadn't it? Father

stumbled from the wooden bedstead where he and Mother slept. Not since Sala had been

weaned had anyone cried out in the night. Was she hungry?

"Grandma died tonight, like a fly in the fire she died!"

Like a squirrel in the fox's teeth, thought Lared. Like a lizard in the cat's mouth,

trembling.

"Of course she's dead," Father said, "but not tonight." He took her in his vast

blacksmith's arms and held her. "Why do you weep now, when Grandma has been dead for

such a long time?" But Sala wept on, as if the grief were great and new.

Then Lared looked at Grandma's old bed. "Father," he whispered. Again, "Father."

For there lay her corpse, still new, still stiffening, though Lared so clearly remembered her

burial long ago.

Father lay Sala back in her truckle bed, where she burrowed down against the woven

straw side, in order not to watch. Lared watched, though, as his father touched the straw tick

beside his old mother's body. "Not cold yet," he murmured. Then he cried out in fear and

agony, "Mother!" Which woke all the sleepers, even the travelers in the room upstairs; they

all came into the sleeping room.

"Do you see it!" cried Father. "Dead a year, at least, and here's her body not yet cold

in her own bed!"

"Dead a year!" cried the old clerk, who had arrived late in the afternoon yesterday, on

a donkey. "Nonsense! She served the soup last night. Don't you remember how she joked

with me that if my bed was too cold, your wife would come up and warm it, and if it was too

warm, she would sleep with me?"

Lared tried to sort out his memories. "I remember that, but I remember that she said

that long, long ago, and yet I remember she said it to you, and I never saw you before last

night."

"I buried you!" Father cried, and then he knelt at Grandma's bed and wept. "I buried

you, and forgot you, and here you are to grieve me!"

Weeping. It was an unaccustomed sound in the village of Flat Harbor, and no one

knew what to do about it. Only hungry infants made such cries, and so Mother said, "Elmo,

will you eat something? Let me fetch you something to eat."

"No!" shouted Elmo. "Don't you see my mother's dead?" And he caught his wife by

the arm and flung her roughly away. She fell over the stool and struck her head against the

table.

This was worse than the corpse lying in the bed, stiff as a dried-out bird. For never in

Lared's life had he seen one human being do harm to another. Father, too, was aghast at his

own temper. "Thano, Thanalo, what have I done?" He scarcely knew how to comfort her as

she lay weeping softly on the floor. No one had needed comfort in all their lives. To all the

others, Father said, "I was so angry. I have never been so angry before, and yet what did she

do? I've never felt such a rage, and yet she did me no harm!"

Who could answer him? Something was bitterly wrong with the world, they could see

that; they had all felt anger in the past, but till now something had always come between the

thought and the act, and calmed them. Now, tonight, that calm was gone. They could feel it

in themselves, nothing soothing their fear, nothing telling them wordlessly, All is well.

Sala raised her head above the edge of her bed and said, "The angels are gone, Mama.

No one watches us anymore."

Mother got up from the floor and stumbled over to her daughter. "Don't be foolish,

child. There are no angels, except in dreams."

There is a lie in my mind, Lared said to himself. The traveler came last night, and

Grandma spoke to him just as he said, and yet my memory is twisted, for I remember the

traveler speaking yesterday, but Grandma answering long ago. Something has bent my

memories, for I remember grieving at her graveside, and yet her grave has not been dug.

Mother looked up at Father in awe. "My elbow still hurts, where it struck the floor,"

she said. "It still hurts very much."

A hurt that lasted! Who had heard of such a thing! And when she lifted her arm,

there was a raw and bleeding scrape on it.

"Have I killed you?" asked Father, wonderingly.

"No," said Mother. "I don't think so."

"Then why does it bleed?"

The old clerk trembled and nodded and his voice quivered as he spoke. "I have read

the books of ancient times," he began, and all eyes turned to him. "I have read the books of

ancient times, and in them the old ones spoke of wounds that bleed like slaughtered attle, and

great griefs when the living suddenly are dead, and anger that turned to blows among people.

But that was long, long ago, when men were still animals, and God was young and

inexperienced."

"What does this mean, then?" asked Father. He was not a bookish man, and so even

more than Lared he thought that men who knew books had answers.

"I don't know," said the clerk. "But perhaps it means that God has gone away, or that

he no longer cares for us."

Lared studied the corpse of Grandma, lying on her bed. "Or is he dead?" Lared asked.

"How can God die?" the old clerk asked with withering scorn. "He has all the power

in the universe."

"Then doesn't he have the power to die if he wants to?"

"Why should I speak with children of things like this?" The clerk got up to go

upstairs, and the other travelers took that as a signal to return to bed.

But Father did not go to bed: he knelt by his old mother's body until daybreak. And

Lared also did not sleep, because he was trying to remember what he had felt inside himself

yesterday that he did not feel now, for something was strange in the way his own eyes looked

out upon the world, and yet he could not remember how it was before. Only Sala and

Mother slept, and they slept together in Mother's and Father's bed.

Before dawn, Lared got up and walked over to his mother, and saw that a scab had

formed on her arm, and the bleeding had stopped. Comforted, he dressed himself and went

out to milk the ewe, which was near the end of its milk. Every bit of the milk was needed for

the cheese press and the butter churn -- winter was coming, and this morning, as the cold

breeze whipped at Lared's hair, this morning he looked to winter with dread. Until today he

had always looked at the future like a cow looking at the pasture, never imagining drought or

snow. Now it was possible for old women to be found dead in their beds. Now it was

possible for Father to be angry and knock Mother to the floor. Now it was possible for

Mother to bleed like an animal. And so winter was more than just a season of inactivity. It

was the end of hope.

The ewe perked up at something, a sound perhaps that Lared was too human to hear.

He stopped milking and looked up, and saw in the western sky a great light, which hovered in

the air like a star that had lost its bearings and needed help to get back home. Then the light

sank down below the level of the trees across the river, and it was gone. Lared did not know

at first what it might be. Then he remembered the word starship from school and wondered.

Starships did not come to Flat Harbor, or even to this continent, or even, more than once a

decade, to this world. Thee was nothing here to carry away to somewhere else, nothing

lacking here that only other worlds could possibly supply. Why, then, would a starship come

here now? Don't be a fool, Lared, he told himself. It was a shooting star, but on this strange

morning you made too much of it, because you are afraid.

At dawn, Flat Harbor came awake, and others gradually made the discovery that had

come to Lared's family in the night. They came, as they always did in cold weather, to

Elmo's house, with its great table and indoor kitchen. They were not surprised to find that

Elmo had not yet built up the fire in his forge.

"I scalded myself on the gruel this morning," said Dinno, Mother's closest friend. She

held up the smoothed skin of her fingers for admiration. "Hurts like it was still in the fire.

Good God," she said.

Mother had her own wounds, but she chose not to tell that tale. "When that old clerk

went to leave this morning, his donkey kicked him square in the belly, and now he's upstairs.

Too much hurt to travel, he says. Threw up his breakfast."

There were a score of minor, careless injuries, and by noon most people were walking

more carefully, carrying out their tasks more slowly. Not a one of them but had some injury.

Omber, one of the diggers of Grandma's grave, crushed his foot with a pick, and it bled for a

long, long time; now, white and weak and barely alive, he lay drawing scant breath in one of

Mother's guest beds. And father, death on his mind, would not even take the hammer in his

hand on the Day of Pain, "For fear I'll strike fire into my eye, or break my hand. God

doesn't look out for us anymore."

They laid Grandma into the ground at noon, and all day Lared and Sala were busy

helping Mother with the work that Grandma used to do. Her place at table was so empty.

Many a sentence began, "Grandma." And Father always looked away as if searching for

something hidden deep in the walls. Try as they might, no one could think of a time before

this when grief had been anything but a dim and wistful memory; never had the loss of a

loved one come so suddenly, with the gap in their lives so plain, with the soil on the grave so

black and rich, fresh as the first-turned fold of earth in the spring plowing.

Late in the afternoon, Omber died, the last blood of his body seeping into the rough

bandage. He lay beside the wide-eyed clerk, who still vomited everything he swallowed and

cried out in pain when he tried to sit. Never in their lives had they seen a man die still in his

strength and prime, and just from a careless blow of a pick.

They were still digging the new grave for Omber when Bran's daughter, Clany, fell

into the fire and lay screaming for three hours before she died. No one could even speak

when they laid her into the third grave of the day. For a village of a scant three hundred

souls, the death of three on the same day would have been calamitous; the death of a strong

man and a young child, that undid them all.

|