|

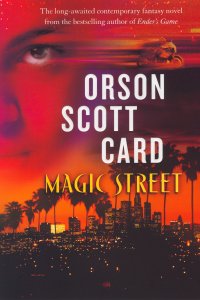

Magic Street

This partial manuscript copy is provided as a courtesy. Anyone who wishes a copy may access it from www.hatrack.com; therefore we ask that no copies, physical or electronic, be given or lent. Any offering of this portion of the manuscript for sale is expressly prohibited.

Chapter Two

Ura Lee's Window

Ura Lee Smitcher looked out the window of her house on the corner of

Burnside and Sanchez as two boys walked by on the other side of the street,

carrying skateboards. "There's your son with that Raymond boy from out on

Coliseum."

Madeline Tucker sat on Ura Lee's couch, drinking coffee. She didn't even

look up from People Magazine. "I know all about Raymo Vine."

"I hope what you know is he's heading for jail, because he is."

"That's exactly what I know," said Madeline. "But what can I do? I

forbid Cecil to see him, and that just guarantees he'll sneak off. Right now

Ceese got no habit of lying to me."

Ura Lee almost said something.

Madeline Tucker didn't miss much. "I know what you going to say."

"I ain't going to say a thing," said Ura Lee, putting on her silkiest,

southernest voice.

"You going to say, What good if he tell you the truth, if what's true is he's

going to hell in a wheelbarrow?"

She was dead on, but Ura Lee wasn't about to say it in so many words.

"I likely would have said 'handbasket,'" said Ura Lee. "Though truth to tell, I

don't know what the hell a handbasket is."

And now it was Madeline's turn to hesitate and refrain from saying what

she was thinking.

"Oh, you don't have to say it," said Ura Lee. "Women who never had a

child, they all expert on raising other women's children."

"I was not going to say that," said Madeline.

"Good thing," said Ura Lee, "because you best remember I chose not to

give you advice. You just guessed what I was thinking, but I refuse to be

blamed for meddling when I didn't say it."

"And I refuse to be blamed for persecuting you when I didn't say it

either."

"You know," said Ura Lee, "we'd get along a lot better if we wasn't a

couple of mind readers."

"Or maybe that's why we get along so good."

"You think those two boys really going to hike up Cloverdale and ride

down on those contraptions?"

"Not all the way down," said Madeline. "One of them always falls off and

gets bloody or sprained or something."

"They didn't walk like boys looking to have some innocent fun with a hill

and some wheels and gravity," said Ura Lee.

"They a special way to walk for that?"

"Jaunty," said Ura Lee. "Those boys looking sneaky."

"Ah," said Madeline.

"Ah? That's all you got to say?"

Madeline sighed. "I already raised Cecil's four older brothers and not one

of them in jail."

"Not one in college, either," said Ura Lee. "Not to criticize, just

observing."

"All of them with decent jobs and making money, and Antwon doing

fine."

Antwon was the one who was buying rental homes all over South Central

and making money from renting week-to-week to people with no green card so

they couldn't make him fix stuff that broke. The kind of landlord that Ura Lee

had been trying to get away from when she saved up and bought this house in

Baldwin Hills when the real estate market bottomed out after the earthquake.

They'd had this argument before, anyway. Madeline thought it made all

the difference in the world that Antwon was exploiting Mexicans. "They got no

right to be in this country anyway," she said. "If they don't like it, they can go

home."

And Ura Lee had answered, "They came here cause they poor and got no

choice, except to look for something better wherever they can find it. Just like

our people getting away from sharecropping or whatever they were putting up

with in Mississippi or Texas or Carolina, wherever they were from."

Then Madeline would go off on how people who never been slaves got no

comparison, and Ura Lee would go off on how the last slave in her family was

her great-great-grandmother and then Madeline would say all black people

were still slaves and then Ura Lee would say, Then why don't your massuh sell

you off stead of listening to you bitch and moan. Then it would start getting

nasty.

Thing about living next door to somebody for all these years is, you

already had all the arguments. If you were going to change each other's minds,

they'd already be changed. And if you were going to feud over it, you'd already

be feuding. So the only other choice was to just shut up and let it go.

"So you saying you going to cut them a little slack even though you know

they scored some weed and they going up to that open space at the hairpin

turn to smoke it," said Ura Lee.

"Up to the 'slack,' that's what I'm saying. How you know they got weed?"

"Cause Ceese keeps slapping his pocket to make sure something's still

there, and if it was a gun it be so heavy his pants fall down, and they ain't

falling, and if it was a condom then it be a girl with him, and Raymo ain't no

girl, so it's weed."

"And you see all that out this magic window."

"It's a good window," said Ura Lee. "I paid extra for this window."

"I paid extra for the rope swing in my yard," said Madeline. "You know

how fast boys grow out of a rope swing? About fifteen minutes."

"So I got the better deal."

"And you sure they going up to that nasty little park at the hairpin turn."

"Where else can kids in Baldwin Hills go to get privacy, they can't drive

yet?"

"You know what?" said Madeline. "You really should be somebody's

mama. Your talent being wasted in this one-woman house."

"Not wasted -- I'm here to give you advice."

"You ought to get you another man, have some babies before too late."

"Already too late," said Ura Lee. "Men ain't looking for women my age

and size, in case you notice."

"Nothing wrong with your size," said Madeline. "You one damn fine-looking woman, especially in that white nurse's uniform. And you make good

money."

"The kind of man looks for a woman who makes good money ain't the

kind of man I want raising no son of mine. They enough lazy moochers in this

world without me going to all the trouble of having a baby just to grow up and

be another."

"Thing I appreciate about you, Ura Lee, you live next door to my Winston

all these years and you never once make eyes at him."

Madeline seemed to think everybody saw Winston Tucker the way she

did -- the handsome young Vietnam vet with a green beret and a smile that

could make a blind woman get a hot flash. Ura Lee had seen that picture on

the wall in the kitchen of their house, so she knew all about what Madeline had

fallen in love with. But that wasn't Winston anymore. He was bald as an egg

now, with a belly that was only cute to a woman who already loved him.

Not that Ura Lee would judge a man on looks alone. But Winston was

also an accountant and a Christian and he couldn't understand that not

everybody wanted to hear about both subjects all the time. Ura Lee once heard

Cooky Peabody say, "What does that man talk about in bed? Jesus or

accounts receivable?"

And Ura Lee wanted to answer her, Assets and arrears. But she didn't

know a single person well enough to tell nasty puns to. So she still had that

witticism stored up, waiting.

Anyway, Madeline thought her husband was so sexy that other women

must be lusting after his flesh, and she'd be the one to know. They were lucky

they had each other. "A woman's got to have self-control if she expects to get

to heaven, Madeline," said Ura Lee.

"The Lord sometimes puts temptation right next door," said Madeline

knowingly, "but then he gives us the strength to resist it, if we try."

"Meanwhile your boy Ceese is going to have his first experience with

recreational herbology."

"If heredity is any guide, he'll puke once and give it up for good."

"Why, is that what happened to Winston when he tried it?"

"I'm talking about me," said Madeline testily. "Cecil takes after me."

"Except for the Y chromosome and the testosterone," said Ura Lee.

"Trust a nurse to get all medical on me."

"Well, Madeline, I say it's nice to have some trust in your children."

"Trust, hell," said Madeline. "I going to tell his daddy when he gets

home, and Cecil's going to be sitting on one butt cheek at a time for a month."

She got up from the couch and started for the kitchen with her coffee

cup. Ura Lee knew from experience that the kitchen was worth another twenty

minutes of conversation, and she didn't like standing around on linoleum, not

after a whole shift on linoleum in the hospital. So she snared the cup and

saucer from Madeline's hand and said, "Oh, don't you bother, I want to sit here

and see more visions of the future out of my window anyway." In a few

minutes the goodbyes were done and Ura Lee was alone.

Alone and thinking, as she washed the cups and saucers and put them

in the drying rack to drip -- she hardly ever bothered with the dishwasher

because it seemed foolish to fire up that whole machine just for the few dishes

she dirtied, living alone. Half the time she nuked frozen dinners and ate them

right off the tray, so there was nothing but a knife and fork to wash up anyway.

What she was thinking was: Madeline and Winston have about the best

marriage I've seen in Baldwin Hills, and they're happy, and their boys are still

nothing but a worry even after they get out of the house. Antwon, who is doing

fine, still had somebody shoot at him the other day when he was collecting

rent, and twice had his tires slashed. And the other boys had no ambition at

all. Just lazy -- completely unlike their father, who, you had to give him credit,

worked hard. And Cecil -- he used to be the best of the lot, but now he was

hanging with Raymo, who was studying up to be completely worthless and had

just about earned his Dumb Ass degree, summa cum scumbag.

Last thing I want in my life is a child. Even if I was good at it -- no

saying I would be, either, because as far as I can tell nobody's actually good at

parenting, just lucky or not -- even if I was good at mothering, I'd probably get

nothing but kids who thought I was the worst mother in the world until I

dropped dead, and then they'd cry about what a good mama I was at my

funeral but a fat lot of good that would do me because I'd be dead.

Of course, maybe I'd have a daughter like me, I was good to my mama till

she got herself smashed up on the 405 the very day I had finally decided to

take the car keys away from her because her reaction time was so slow I was

afraid she was going to kill somebody running a stop sign. If I had taken the

keys away from her, then she'd be alive but she'd hate me for keeping her from

having the freedom of driving a car. What good is a good daughter if the only

way she can be good to you is make your life miserable?

Not to mention how unhappy it made Mama when Ura Lee up and

married that ridiculous Willie Joe Smitcher, who thought he was born with a

golden key behind the zipper of his pants and had to slide it into every lock he

could get near to, just in case it was the gate of heaven. And people wondered

why Ura Lee didn't have kids! Knowing, as a nursing student, just what the

chances were of Willie Joe picking up something nasty, she had no choice but

to protect her own health by keeping that golden key rubber-wrapped at home.

She told him that when he was faithful to her for long enough that she could

be sure he was clean, the wrapping could come off, but he chose the other

alternative and they went their separate ways with the government's

permission before she even got her first job as a nurse. And, give the boy

credit, he never came back to her asking for money. He wasn't a mooch, he

was just a man who thought he had a mission to perform, like Johnny

Appleseed, except for the apples.

It only means that I'll never have a son like him, or a daughter foolish

enough to marry a man like him, and that makes me about as happy a woman

as lives on Burnside, and that's saying something, because by and large this is

a pretty happy street. People here got some money, but not serious money, not

Brentwood or Beverly Hills money, and sure as hell not Malibu beachfront

money. Just comfortable money, a little bit of means. And only a block away

from Cloverdale, and that street have real money, on up the hill, anyway.

She only got into Baldwin Hills herself because the earthquake knocked

this house a little bit off its foundation and her mama left her just enough

money to get over the top for a down payment -- a fluke. But she was happy

here. These were good people. She'd watch them raise their children, and

suffer all that anxiety all the time, and thank God she didn't have such a

burden in her own life.

Copyright © 2005 Orson Scott Card

|