[Part of the Alvin Maker series, this story falls chronologically between Heartfire and The Crystal City.]

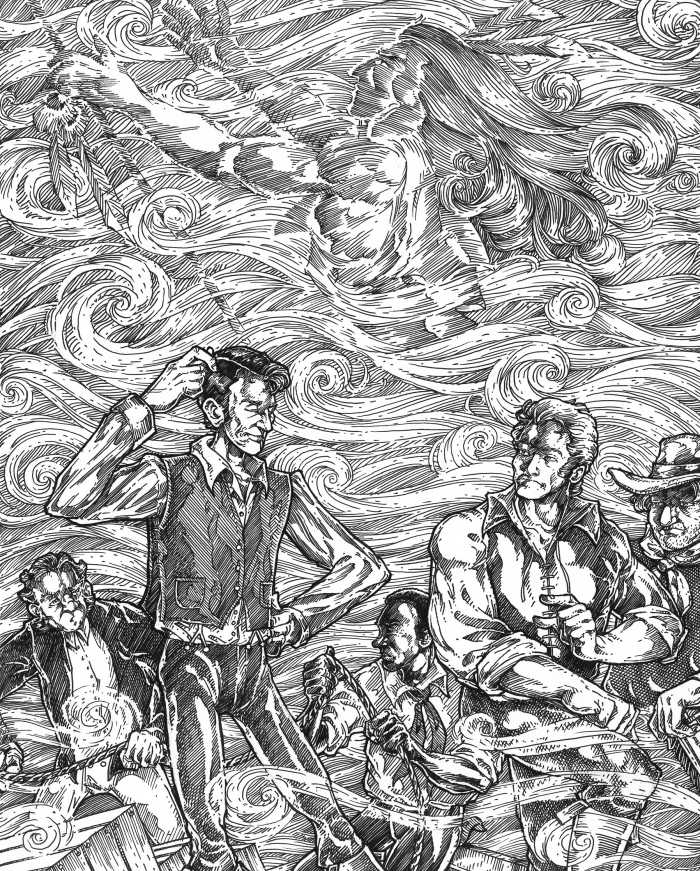

Alvin watched as Captain Howard welcomed aboard another group of passengers, a prosperous family with five children and three slaves.

"It's the Nile River of America," said the captain. "But Cleopatra herself never sailed in such splendor as you folks is going to experience on the Yazoo Queen."

Splendor for the family, thought Alvin. Not likely to be much splendor for the slaves -- though, being house servants, they'd fare better than the two dozen runaways chained together in the blazing sun at dockside all afternoon.

Alvin had been keeping an eye on them since he and Arthur Stuart got here to the Carthage City riverport at eleven. Arthur Stuart was all for exploring, and Alvin let him go. The city that billed itself as the Phoenicia of the West had plenty of sights for a boy Arthur's age, even a half-black boy. Since it was on the north shore of the Hio, there'd be suspicious eyes on him for a runaway. But there was plenty of free blacks in Carthage City, and Arthur Stuart was no fool. He'd keep an eye out.

There was plenty of slaves in Carthage, too. That was the law, that a black slave from the South remained a slave even in a free state. And the greatest shame of all was those chained-up runaways who got themselves all the way across the Hio to freedom, only to be picked up by Finders and dragged back in chains to the whips and other horrors of bondage. Angry owners who'd make an example of them. No wonder there was so many who killed theirselves, or tried to.

Alvin saw wounds on more than a few in this chained-up group of twenty-five, though many of the wounds could have been made by the slave's own hand. Finders weren't much for injuring the property they was getting paid to bring on home. No, those wounds on wrists and bellies were likely a vote for freedom before life itself.

What Alvin was watching for was to know whether the runaways were going to be loaded on this boat or another. Most often runaways were ferried across river and made to walk home over land -- there was too many stories of slaves jumping overboard and sinking to the bottom with their chains on to make Finders keen on river transportation.

But now and then Alvin had caught a whiff of talking from the slaves -- not much, since it could get them a bit of lash, and not loud enough for him to make out the words, but the music of the language didn't sound like English, not northern English, not southern English, not slave English. It wasn't likely to be any African language. With the British waging full-out war on the slave trade, there weren't many new slaves making it across the Atlantic these days.

So it might be Spanish they were talking, or French. Either way, they'd most likely be bound for Nueva Barcelona, or New Orleans, as the French still called it.

Which raised some questions in Alvin's mind. Mostly this one: How could a bunch of Barcelona runaways get themselves to the state of Hio? That would have been a long trek on foot, especially if they didn't speak English. Alvin's wife, Peggy, grew up in an Abolitionist home, with her Papa, Horace Guester, smuggling runaways across river. Alvin knew something about how good the Underground Railway was. It had fingers reaching all the way down into the new duchies of Mizzippy and Alabam, but Alvin never heard of any Spanish- or French-speaking slaves taking that long dark road to freedom.

"I'm hungry again," said Arthur Stuart.

Alvin turned to see the boy -- no, the young man, he was getting so tall and his voice so low -- standing behind him, hands in his pockets, looking at the Yazoo Queen.

"I'm a-thinking," said Alvin, "as how instead of just looking at this boat, we ought to get on it and ride a spell."

"How far?" asked Arthur Stuart.

"You asking cause you're hoping it's a long way or a short one?"

"This one goes clear to Barcy."

"It does if the fog on the Mizzippy lets it," said Alvin.

Arthur Stuart made a goofy face at him. "Oh, that's right, cause around you that fog's just bound to close right in."

"It might," said Alvin. "Me and water never did get along."

"When you was a little baby, maybe," said Arthur Stuart. "Fog does what you tell it to do these days."

"You think," said Alvin.

"You showed me your own self."

"I showed you with smoke from a candle," said Alvin, "and just because I can do it don't mean that every fog or smoke you see is doing what I say."

"Don't mean it ain't, either," said Arthur Stuart, grinning.

"I'm just waiting to see if this boat's a slave ship or not," said Alvin.

Arthur Stuart looked over where Alvin was looking, at the runaways. "Why don't you just turn them loose?" he asked.

"And where would they go?" said Alvin. "They're being watched."

"Not all that careful," said Arthur Stuart. "Them so-called guards has got jugs that ain't close to full by now."

"The Finders still got their sachets. It wouldn't take long to round them up again, and they'd be in even more trouble."

"So you ain't going to do a thing about it?"

"Arthur Stuart, I can't just pry the manacles off every slave in the South."

"I seen you melt iron like it was butter," said Arthur Stuart.

"So a bunch of slaves run away and leave behind puddles of iron that was once their chains," said Alvin. "What do the authorities think? There was a blacksmith snuck in with a teeny tiny bellows and a ton of coal and lit him a fire that het them chains up? And then he run off after, taking all his coal with him in his pockets?"

Arthur Stuart looked at him defiantly. "So it's all about keeping you safe."

"I reckon so," said Alvin. "You know what a coward I am."

Last year, Arthur Stuart would have blinked and said he was sorry, but now that his voice had changed the word "sorry" didn't come so easy to his lips. "You can't heal everybody, neither," he said, "but that don't stop you from healing some."

"No point in freeing them as can't stay free," said Alvin. "And how many of them would run, do you think, and how many drown themselves in the river?"

"Why would they do that?"

"Because they know as well as I do, there ain't no freedom here in Carthage City for a runaway slave. This town may be the biggest on the Hio, but it's more southern than northern, when it comes to slavery. There's even buying and selling of slaves here, they say, flesh markets hidden in cellars, and the authorities know about it and don't do a thing because there's so much money in it."

"So there's nothing you can do."

"I healed their wrists and ankles where the manacles bite so deep. I cooled them in the sun and cleaned the water they been given to drink so it don't make them sick."

Now, finally, Arthur Stuart looked a bit embarrassed -- though still defiant. "I never said you wasn't nice," he said.

"Nice is all I can be," said Alvin. "In this time and place. That and I don't plan to give my money to this captain iffen the slaves are going southbound on his boat. I won't help pay for no slave ship."

"He won't even notice the price of our passage."

"Oh, he'll notice, all right," said Alvin. "This Captain Howard is a fellow what can tell how much money you got in your pocket by the smell of it."

"You can't even do that," said Arthur Stuart.

"Money's his knack," said Alvin. "That's my guess. He's got him a pilot to steer the ship, and an engineer to keep that steam engine going, and a carpenter to tend the paddlewheel and such damage as the boat takes passing close to the left bank all the way down the Mizzippy. So why is he captain? It's about the money. He knows who's got it, and he knows how to talk it out of them."

"So how much money's he going to think you got?"

"Enough money to own a big young slave, but not enough money to afford one what doesn't have such a mouth on him."

Arthur Stuart glared. "You don't own me."

"I told you, Arthur Stuart, I didn't want you on this trip and I still don't. I hate taking you south because I have to pretend you're my property, and I don't know which is worse, you pretending to be a slave, or me pretending to be the kind of man as would own one."

"I'm going and that's that."

"So you keep on saying," said Alvin.

"And you must not mind because you could force me to stay here iffen you wanted."

"Don't say 'iffen,' it drives Peggy crazy when you do."

"She ain't here and you say it your own self."

"The idea is for the younger generation to be an improvement over the older."

"Well, then, you're a mizzable failure, you got to admit, since I been studying makering with you for lo these many years and I can barely make a candle flicker or a stone crack."

"I think you're doing fine, and you're better than that, anyway, if you just put your mind to it."

"I put my mind to it till my head feels like a cannonball."

"I suppose I should have said, Put your heart in it. It's not about making the candle or the stone -- or the iron chains, for that matter -- it's not about making them do what you want, it's about getting them to do what you want."

"I don't see you setting down and talking no iron into bending or dead wood into sprouting twigs, but they do it."

"You may not see me or hear me do it, but I'm doing it all the same, only they don't understand words, they understand the plan in my heart."

"Sounds like making wishes to me."

"Only because you haven't learned yourself how to do it yet."

"Which means you ain't much of a teacher."

"Neither is Peggy, what with you still saying 'ain't'."

"Difference is, I know how not to say 'ain't' when she's around to hear it," said Arthur Stuart, "only I can't poke out a dent in a tin cup whether you're there or not."

"Could if you cared enough," said Alvin.

"I want to ride on this boat."

"Even if it's a slave ship?" said Alvin.

"Us staying off ain't going to make it any less a slave ship," said Arthur Stuart.

"Ain't you the idealist."

"You ride this Yazoo Queen, Master of mine, and you can keep those slaves comfy all the way back to hell."

The mockery in his tone was annoying, but not misplaced, Alvin decided.

"I could do that," said Alvin. "Small blessings can feel big enough, when they're all you got."

"So buy the ticket, cause this boat's supposed to sail first thing in the morning, and we want to be aboard already, don't we?"

Alvin didn't like the mixture of casualness and eagerness in Arthur Stuart's words. "You don't happen to have some plan to set these poor souls free during the voyage, do you? Because you know they'd jump overboard and there ain't a one of them knows how to swim, you can bet on that, so it'd be plain murder to free them."

"I got no such plan."

"I need your promise you won't free them."

"I won't life a finger to help them," said Arthur Stuart. "I can make my heart as hard as yours whenever I want."

"I hope you don't think that kind of talk makes me glad to have your company," said Alvin. "Specially because I think you know I don't deserve it."

"You telling me you don't make your heart hard, to see such sights and do nothing?"

"If I could make my heart hard," said Alvin, "I'd be a worse man, but a happier one."

Then he went off to the booth where the Yazoo Queen's purser was selling passages. Bought him a cheap ticket all the way to Nueva Barcelona, and a servant's passage for his boy. Made him angry just to have to say the words, but he lied with his face and the tone of his voice and the purser didn't seem to notice anything amiss. Or maybe all slave owners were just a little angry with themselves, so Alvin didn't seem much different from any other.

Plain truth of it was, Alvin was about as excited to make this voyage as a man could get. He loved machinery, all the hinges, pistons, elbows of metal, the fire hot as a smithy, the steam pent up in the boilers. He loved the great paddlewheel, turning like the one he grew up with at his father's mill, except here it was the wheel pushing the water, stead of the water pushing the wheel. He loved feeling the strain on the steel -- the torque, the compression, the levering, the flexing and cooling. He sent out his doodlebug and wandered around inside the machines, so he'd know it all like he knew his own body.

The engineer was a good man who cared well for his machine, but there was things he couldn't know. Small cracks in the metal, places where the stress was too much, places where the grease wasn't enough and the friction was a-building up. Soon as he understood how it ought to be, Alvin began to teach the metal how to heal itself, how to seal the tiny fractures, how to smooth itself so the friction was less. That boat wasn't more than two hours out of Carthage before he had the machinery about as perfect as a steam engine could get, and then it was just a matter of riding with it. His body, like everybody else's, riding on the gently shifting deck, and his doodlebug skittering through the machinery to feel it pushing and pulling.

But soon enough it didn't need his attention any more, and so the machinery moved to the back of his mind while he began to take an interest in the goings-on among the passengers.

There was people with money in the first-class cabins, with their servants' quarters close at hand. And then people like Alvin, with only a little coin, but enough for the second-class cabins, where there was four passengers to the room. All their servants, them as had any, was forced to sleep below decks like the crew, only even more cramped, not because there wasn't room to do better, but because the crew was bound to get surly iffen their bed was as bad as a blackamoor's.

And finally there was the steerage passengers, who didn't even have no beds, but just benches. Them as was going only a short way, a day's journey or so, it made plain good sense to go steerage. But a good many was just poor folks bound for some far-off destination, like Thebes or Corinth or Barcy itself, and if their butts got sore on the benches, well, it wouldn't be the first pain they suffered in their life, nor would it be their last.

Still, Alvin felt like it was kind of his duty, being as how it took him so little effort, to sort of shape the benches to the butts that sat on them. And it took no great trouble to get the lice and bedbugs to move on up to the first class cabins. Alvin thought of it as kind of an educational project, to help the bugs get a taste of the high life. Blood so fine must be like fancy likker to a louse, and they ought to get some knowledge of it before their short lives was over.

All this took Alvin's concentration for a good little while. Not that he ever gave it his whole attention -- that would be too dangerous, in their world where he had enemies out to kill him, and strangers as would wonder what was in his bag that he kept it always so close at hand. So he kept an eye out for all the heartfires on the boat, and if any seemed coming a-purpose towards him, he'd know it, right enough.

Except it didn't work that way. He didn't sense a soul anywheres near him, and then there was a hand right there on his shoulder, and he like to jumped clean overboard with the shock of it.

"What the devil are you -- Arthur Stuart, don't sneak up on a body like that."

"It's hard not to sneak with the steam engine making such a racket," said Arthur, but he was a-grinnin' like old Davy Crockett, he was so proud of himself.

"Why is it the one skill you take the trouble to master is the one that causes me the most grief?" asked Alvin.

"I think it's good to know how to hide my ... heartfire." He said the last word real soft, on account of it didn't do to talk about makery where others might hear and get too curious.

Alvin taught the skill freely to all who took it serious, but he didn't put on a show of it to inquisitive strangers, especially because there was no shortage of them as would remember hearing tales of the runaway smith's apprentice who stole a magic golden plowshare. Didn't matter that the tale was three-fourths fantasy and nine-tenths lie. It could get Alvin kilt or knocked upside the head and robbed all the same, and the one part that was true was that living plow inside his poke, which he didn't want to lose, specially not now after carrying it up and down America for half his life now.

"Ain't nobody on this boat can see your heartfire ceptin' me," said Alvin. "So the only reason for you to learn to hide is to hide from the one person you shouldn't hide from anyhow."

"That's plain dumb," said Arthur Stuart. "If there's one person a slave has to hide from, it's his master."

Alvin glared at him. Arthur grinned back.

A voice boomed out from across the deck. "I like to see a man who's easy with his servants!"

Alvin turned to see a smallish man with a big smile and a face that suggested he had a happy opinion of himself.

"My name's Austin," said the fellow. "Stephen Austin, attorney at law, born, bred, and schooled in the Crown Colonies, and now looking for people as need legal work out here on the edge of civilization."

"The folks on either hand of the Hio like to think of theirselves as mostwise civilized," said Alvin, "but then, they haven't been to Camelot to see the King."

"Was I imagining that I heard you speak to your boy there as 'Arthur Stuart'?"

"It was someone else's joke at the naming of the lad," said Alvin, "but I reckon by now the name suits him." All the time Alvin was thinking, what does this man want, that he'd trouble to speak to a sun-browned, strong-armed, thick-headed-looking wight like me?

He could feel a breath for speech coming up in Arthur Stuart, but the last thing Alvin wanted was to deal with whatever fool thing the boy might take it into his head to say. So he gripped him noticeably on the shoulder and it just kind of squeezed the air right out of him without more than a sigh.

"I noticed you've got shoulders on you," said Austin.

"Most folks do," said Alvin. "Two of 'em, nicely matched, one to an arm."

"I almost thought you might be a smith, except smiths always have one huge shoulder, and the other more like a normal man's."

"Except such smiths as use their left hand exactly as often as their right, just so they keep their balance."

Austin chuckled. "Well, then, that solves the mystery. You are a smith."

"When I got me a bellows, and charcoal, and iron, and a good pot."

"I don't reckon you carry that around with you in your poke."

"Sir," said Alvin, "I been to Camelot once, and I don't recollect as how it was good manners there to talk about a man's poke or his shoulders neither, upon such short acquaintance."

"Well, of course, it's bad manners all around the world, I'd say, and I apologize. I meant no disrespect. Only I'm recruiting, you see, them as has skills we need, and yet who don't have a firm place in life. Wandering men, you might say."

"Lots of men a-wanderin'," said Alvin, "and not all of them are what they claim."

"But that's why I've accosted you like this, my friend," said Austin. "Because you weren't claiming a blessed thing. And on the river, to meet a man with no brag is a pretty good recommendation."

"Then you're new to the river," said Alvin, "because many a man with no brag is afraid of gettin' recognized."

"Recognized," said Austin. "Not 'reckonize.' So you've had you some schooling."

"Not as much as it would take to turn a smith into a gentleman."

"I'm recruiting," said Austin. "For an expedition."

"Smiths in particular need?"

"Strong men good with tools of all kinds," said Austin.

"Got work already, though," said Alvin. "And an errand in Barcy."

"So you wouldn't be interested in trekking out into new lands, which are now in the hands of bloody savages, awaiting the arrival of Christian men to cleanse the land of their awful sacrifices?"

Alvin instantly felt a flush of anger mixed with fear, and as he did whenever so strong a feeling came over him, he smiled brighter than ever and kept hisself as calm as could be. "I reckon you'd have to brave the fog and cross to the west bank of the river for that," said Alvin. "And I hear the Reds on that side of the river has some pretty powerful eyes and ears, just watching for Whites as think they can take war into peaceable places."

"Oh, you misunderstood me, my friend," said Austin. "I'm not talking about the prairies where one time trappers used to wander and now the Reds won't let no white man pass."

"So what savages did you have in mind?'

"South, my friend, south and west. The evil Mexica tribes, that vile race that tears the heart out of a living man upon the tops of their ziggurats."

"That's a long trek indeed," said Alvin. "And a foolish one. What the might of Spain couldn't rule, you think a few Englishmen with a lawyer at their head can conquer?"

By now Austin was leaning on the rail beside Alvin, looking out over the water. "The Mexica have become rotten. Hated by the other Reds they rule, dependent on trade with Spain for second-rate weaponry -- I tell you it's ripe for conquest. Besides, how big an army can they put in the field, after killing so many men on their altars for all these centuries?"

"It's a fool as goes looking for a war that no one brought to him."

"Aye, a fool, a whole passel of fools. The kind of fools as wants to be as rich as Pizzarro, who conquered the great Inca with a handful of men."

"Or as dead as Cortez?"

"They're all dead now," said Austin. "Or did you think to live forever?"

Alvin was torn between telling the fellow to go pester someone else and leading him on so he could find out more about what he was planning. But in the long run, it wouldn't do to become too familiar with this fellow, Alvin decided. "I reckon I've wasted your time up to now, Mr. Austin. There's others are bound to be more interested than I am, since I got no interest at all."

Austin smiled all the more broadly, but Alvin saw how his pulse leapt up and his heartfire blazed. A man who didn't like being told no, but hid it behind a smile.

"Well, it's good to make a friend all the same," said Austin, sticking out his hand.

"No hard feelings," said Alvin, "and thanks for thinking of me as a man you might want at your side."

"No hard feelings indeed," said Austin, "and though I won't ask you again, if you change your mind I'll greet you with a ready heart and hand."

They shook on it, clapped shoulders, and Austin went on his way without a backward glance.

"Well, well," said Arthur Stuart. "What do you want to bet it isn't no invasion or war, but just a raiding party bent on getting some of that Mexica gold?"

"Hard to guess," said Alvin. "But he talks free enough, for a man proposing to do something forbidden by King and by Congress. Neither the Crown Colonies nor the United States would have much patience with him if he was caught."

"Oh, I don't know," said Arthur Stuart. "The law's one thing, but what if King Arthur got it in his head that he needed more land and more slaves and didn't want a war with the U.S.A. to get it?"

"Now there's a thought," said Alvin.

"A pretty smart thought, I think," said Arthur Stuart.

"It's doing you good, traveling with me," said Alvin. "Finally getting some sense into your head."

"I thought of it first," said Arthur Stuart.

In answer, Alvin took a letter out of his pocket and showed it to the boy.

"It's from Miz Peggy," said Arthur. He read for a moment. "Oh, now, don't tell me you knew this fellow was going to be on the boat."

"I most certainly did not have any idea," said Alvin. "I figured my inquiries would begin in Nueva Barcelona. But now I've got a good idea whom to watch when we get there."

"She talks about a man named Burr," said Arthur Stuart.

"But he'd have men under him," said Alvin. "Men to go out recruiting for him, iffen he hopes to raise an army."

"And he just happened to walk right up to you."

"He just happened to listen to you sassing me," said Alvin, "and figured I wasn't much of a master, so maybe I'd be a natural follower."

Arthur Stuart folded up the letter and handed it back to Alvin. "So if the King is putting together an invasion of Mexico, what of it?"

"Iffen he's fighting the Mexica," said Alvin, "he can't be fighting the free states, now, can he?"

"So maybe the slave states won't be so eager to pick a fight," said Arthur Stuart.

"But someday the war with Mexico will end," said Alvin. "Iffen there is a war, that is. And when it ends, either the King lost, in which case he'll be mad and ashamed and spoilin' for trouble, or he won, in which case he'll have a treasury full of Mexica gold, able to buy him a whole navy iffen he wants."

"Miz Peggy wouldn't be too happy to hear you sayin' 'iffen' so much."

"War's a bad thing, when you take after them as haven't done you no harm, and don't mean to."

"But wouldn't it be good to stop all that human sacrifice?"

"I think the Reds as are prayin' for relief from the Mexica don't exactly have slavers in mind as their new masters."

"But slavery's better than death, ain't it?"

"Your mother didn't think so," said Alvin. "And now let's have done with such talk. It just makes me sad."

"To think of human sacrifice? Or slavery?"

"No. To hear you talk as if one was better than the other." And with that dark mood on him, Alvin walked to the room that so far he had all to himself, set the golden plow upon the bunk, and curled up around it to think and doze and dream a little and see if he could understand what it all meant, to have this Austin fellow acting so bold about his project, and to have Arthur Stuart be so blind, when so many people had sacrificed so much to keep him free.

It wasn't till they got to Thebes that another passenger was assigned to Alvin's cabin. He'd gone ashore to see the town -- which was being touted as the greatest city on the American Nile -- and when he came back, there was a man asleep on the very bunk where Alvin had been sleeping.

Which was irksome, but understandable. It was the best bed, being the lower bunk on the side that got sunshine in the cool of the morning instead of the heat of the afternoon. And it's not as if Alvin had left any possessions in the cabin to mark the bed as his own. He carried his poke with him when he left the boat, and all his worldly goods was in it. Lessen you counted the baby that his wife carried inside her -- which, come to think of it, she carried around with her about as constantly as Alvin carried that golden plow.

So Alvin didn't wake the fellow up. He just turned and left, looking for Arthur Stuart or a quiet place to eat the supper he'd brought on board. Arthur had insisted he wanted to stay aboard, and that was fine with Alvin, but he was blamed if he was going to hunt him down before eating. It wasn't no secret that the whistle had blowed the signal for everyone to come aboard. So Arthur Stuart should have been watching for Alvin, and he wasn't.

Not that Alvin doubted where he was. He could key right in on Arthur's heartfire most of the time, and he doubted the boy could hide from him if Alvin was actually seeking him out. Right now he knew that the boy was down below in the slave quarters, a place where no one would ask him his business or wonder where his master was. What he was about was another matter.

Almost as soon as Alvin opened up his poke to take out the cornbread and cheese and cider he'd brought in from town, he could see Arthur start moving up the ladderway to the deck. Not for the first time, Alvin wondered just how much the boy really understood of makering.

Arthur Stuart wasn't a liar by nature, but he could keep a secret, more or less, and wasn't it just possible that he hadn't quite got around to telling Alvin all that he'd learned how to do? Was there a chance the boy picked that moment to come up because he knew Alvin was back from town, and knew he was setting hisself down to eat?

Sure enough, Alvin hadn't got but one bite into his first slice of bread and cheese when Arthur Stuart plunked himself down beside him on the bench. Alvin could've eaten in the dining room, but there it would have given offense for him to let his "servant" set beside him. Out on the deck, it was nobody's business. Might make him look low class, in the eyes of some slaveowners, but Alvin didn't much mind what slaveowners thought of him.

"What was it like?" asked Arthur Stuart.

"Bread tastes like bread."

"I didn't mean the bread, for pity's sake!"

"Cheese is pretty good, despite being made from milk that come from the most measly, mangy, scrawny, fly-bit, sway-backed, half-blind, bony-hipped, ill-tempered, cud-pukin', sawdust-fed bunch of cattle as ever teetered on the edge of the grave."

"So they don't specialize in fine dairy, is what you're saying."

"I'm saying that if Thebes is spose to be the greatest city on the American Nile, they might oughta start by draining the swamp. I mean, the reason the Hio and the Mizzippy come together here is because it's low ground, and being low ground it gets flooded a lot. It didn't take no scholar to figure that out."

"Never heard of a scholar who knowed low ground from high, anyhow."

"Now, Arthur Stuart, it's not a requirement that scholars be dumb as mud about ... well, mud."

"Oh, I know. Somewhere there's bound to be a scholar who's got book-learnin' and common sense, both. He just hasn't come to America."

"Which I spose is proof of the common sense part, bein' as this is the sort of country where they build a great city in the middle of a bog."

They chuckled together and then filled up their mouths too much for talking.

When the food was gone -- and Arthur had et more than half of it, and looked like he was wishing for more -- Alvin asked him, pretending to be all casual about it, "So what was so interesting down with the servants in the hold?"

"The slaves, you mean?"

"I'm trying to talk like the kind of person as would own one," said Alvin very softly. "And you ought to try to talk like the kind of person as was owned. Or don't come along on trips south."

"I was trying to find out what language those score-and-a-quarter chained-up runaways was talking."

"And?"

"Ain't French, cause there's a cajun what says not. Ain't Spanish, cause there's a fellow grew up in Cuba what says not. Nary a soul knew their talk."

"Well, at least we know what they're not."

"I know more than that," said Arthur Stuart.

"I'm listening."

"The Cuba fellow, he takes me aside and he says, Tell you what, boy, I think I hear me their kind talk afore, and I says, what's their language, and he says, I think they be no kind runaway."

"Why's he think that?" said Alvin. But inside, he's noticing the way Arthur Stuart picks up exactly the words the fellow said, and the accent, and he remembers how it used to be when Arthur Stuart could do any voice he heard, a perfect mimic. And not just human voices, neither, but bird calls and animal cries, and a baby crying, and the wind in the trees or the scrape of a shoe on dirt. But that was before Alvin changed him, deep inside, changed the very smell of him so that the Finders couldn't match him up to his sachet no more. He had to change him in the smallest, most hidden parts of him. Cost him part of his knack, it did, and that was a harsh thing to do to a child. But it also saved his freedom. Alvin couldn't regret doing it. But he could regret the cost.

"He says, I hear me their kind talk aforeday, long day ago, when I belong a massuh go Mexico."

Alvin nodded wisely, though he had no idea what this might mean.

"And I says to him, How come black folk be learning Mexica talk? And he says, They be black folk all over Mexico, from aforeday."

"That would make sense," said Alvin. "The Mexica only threw the Spanish out fifty years ago. I reckon they was inspired by Tom Jefferson getting Cherriky free from the King. Spanish must've brought plenty of slaves to Mexico up to then."

"Well, sure," said Arthur Stuart. "So I was wondering, if the Mexica kill so many sacrifices, why didn't they use up these African slaves first? And he says, Black man dirty, Mexica no can cook him up for Mexica god. And then he just laughed and laughed."

"I guess there's advantages to having folks think you're impure by nature."

"Heard a lot of preachers in America say that God thinks all men is filthy at heart."

"Arthur Stuart, I know that's a falsehood, because in your life you never been to hear a lot of preachers say a blame thing."

"Well, I heard of preachers saying such things. Which explains why our God don't hold with human sacrifice. Ain't none of us worthy, white or black."

"Except I don't think that's the opinion God has of his children," said Alvin, "and neither do you."

"I think what I think," said Arthur Stuart. "Ain't always the same thing as you."

"I'm just happy you've taken up thinkin' at all," said Alvin.

"As a hobby," said Arthur Stuart. "I ain't thinkin' of takin' it up as a trade or nothin'."

Alvin gave a chuckle, and Arthur Stuart settled back to enjoy it.

Alvin got to thinking out loud. "So. We got us twenty-five slaves who used to belong to the Mexica. Only now they're going down the Mizzippy on the very same boat as a man recruiting soldiers for an expedition against Mexico. That's a downright miraculous coincidence."

"Guides?" said Arthur Stuart.

"I reckon that's likely. Maybe they're wearing chains for the same reason you're pretending to be a slave. So people will think they're one thing, when actually they're another."

"Or maybe somebody's so dumb he thinks that chained-up slaves will be good guides through uncharted land."

"So you're saying maybe they won't be reliable."

"I'm saying maybe they think starving to death all lost in the desert ain't a bad way to die, if they can take some white slaveowners with them."

Alvin nodded. The boy did understand that slaves might prefer death, after all. "Well, I don't speak Mexica, and neither do you."

"Yet," said Arthur Stuart.

"Don't see how you'll learn it," said Alvin. "They don't let nobody near 'em."

"Yet," said Arthur Stuart.

"I hope you ain't got some damn fool plan going on in your head that you're not going to tell me about."

"Don't mind telling you. I already got me a turn feeding them and picking up their slop bucket. The pre-dawn turn, which nobody belowdecks is hankering to do."

"They're guarded day and night. How you going to start talking to them anyway?"

"Come on now, Alvin, you know there must be at least one of them speaks English, or how would they be able to guide anybody anywhere?"

"Or one of them speaks Spanish, and one of the slaveowners speaks it too, you ever think of that?"

"That's why I got the Cuba fellow to teach me Spanish."

That was brag. "I was only gone into town for six hours, Arthur Stuart."

"Well, he didn't teach me all of it."

That set Alvin to wondering once again if Arthur Stuart had more of his knack left than he ever let on. Learn a language in six hours? Of course, there was no guarantee that the Cuban slave knew all that much Spanish, any more than he knew all the much English. But what if Arthur Stuart had him a knack for languages? What if he'd never been a mimic at all, but instead a natural speaker-of-all-tongues? There was tales of such -- of men and women who could hear a language and speak it like a native right from the start.

Did Arthur Stuart have such a knack? Now that the boy was becoming a man, was he getting a real grasp of it? For a moment Alvin caught himself being envious. And then he had to laugh at himself -- imagine a fellow with his knack, envying somebody else. I can make rock flow like water, I can make water as strong as steel and as clear as glass, I can turn iron into living gold, and I'm jealous because I can't also learn languages the way a cat learns to land on its feet? The sin of ingratitude, just one of many that's going to get me sent to hell.

"What're you laughing at?" asked Arthur Stuart.

"Just appreciating that you're not a mere boy any more. I trust that if you need any help from me -- like somebody catches you talking to them Mexica slaves and starts whipping you -- you'll contrive some way to let me know that you need some help?"

"Sure. And if that knife-wielding killer who's sleeping in your bed gets troublesome, I expect you'll find some way to let me know what you want written on your tombstone?" Arthur Stuart grinned at him.

"Knife-wielding killer?" Alvin asked.

"That's the talk belowdecks. But I reckon you'll just ask him yourself, and he'll tell you all about it. That's how you usually do things, isn't it?"

Alvin nodded. "I spose I do start out asking pretty direct what I want to know."

"And so far you mostly haven't got yourself killed," said Arthur Stuart.

"My average is pretty good so far," said Alvin modestly.

"Haven't always found out what you wanted to know, though," said Arthur Stuart.

"But I always find out something useful," said Alvin. "Like, how easy it is to get some folks riled."

"If I didn't know you had another, I'd say that was your knack."

"Rilin' folks."

"They do get mad at you pretty much when you say hello, sometimes," said Arthur Stuart.

"Whereas nobody ever gets mad at you."

"I'm a likeable fellow," said Arthur Stuart.

"Not always," said Alvin. "You got a bit of brag in you that can be annoying sometimes."

"Not to my friends," said Arthur, grinning.

"No," Alvin conceded. "But it drives your family insane."

By the time Alvin got to his room, the "knife-wielding killer" had woke up from his nap and was somewhere else. Alvin toyed with sleeping in the very same bed, which had been his first, after all. But that was likely to start a fight, and Alvin just plain didn't care all that much. He was glad to have a bed at all, come to think of it, and with four bunks in the room to share between two men, there was no call to be provoking anybody over who got to which one first.

Drifting off to sleep, Alvin reached out as he always did, seeking Peggy, making sure from her heartfire that she was all right. And then the baby, growing fine inside her, had a heartbeat now. Not going to end like the first pregnancy, with a baby born too soon so it couldn't get its breath. Not going to watch it gasp its little life away in a couple of desperate minutes, turning blue and dying in his arms while he frantically searched inside it for some way to fix it so's it could live. What good is it to be a seventh son of a seventh son if the one person you can't heal is your own firstborn baby?

Alvin and Peggy clung together for the first days after that, but then over the weeks to follow she began to grow apart from him, to avoid him, until he finally realized that she was keeping him from being with her to make another baby. He talked with her then, about how you couldn't hide from it, lots of folks lost babies, and half-growed children too, the thing to do was try again, have another, and another, to comfort you when you thought about the little body in the grave.

"I grew up with two graves before my eyes," she said, "and knowing how my parents looked at me and saw my dead sisters with the same name as me."

"Well you was a torch, so you knew more than children ought to know about what goes on inside folks. Our baby most likely won't be a torch. All she'll know is how much we love her and how much we wanted her."

He wasn't sure he so much persuaded her to want another baby as she decided to try again just to make him happy. And during this pregnancy, just like last time, she kept gallivanting up and down the country, working for abolition even as she tried to find some way to bring about freedom short of war. While Alvin stayed in Vigor Church or Hatrack River, teaching them as wanted to learn the rudiments of makery.

Until she had an errand for him, like now. Sending him downriver on a steamboat to Nueva Barcelona, when in his secret heart he just wished she'd stay home with him and let him take care of her.

Course, being a torch she knew perfectly well that was what he wished for, it was no secret at all. So she must need to be apart from him more than he needed to be with her, and he could live with that.

Couldn't stop him from looking for her on the skirts of sleep, and dozing off with her heartfire and the baby's, so bright in his mind.

He woke in the dark, knowing something was wrong. It was a heartfire right up close to him; then he heard the soft breath of a stealthy man. With his doodlebug he got inside the man and felt what he was doing -- reaching across Alvin toward the poke that was tucked in the crook of his arm.

Robbery? On board a riverboat was a blame foolish time for it, if that was what the man had in mind. Unless he was a good enough swimmer to get to shore carrying a heavy golden plowshare.

The man carried a knife in a sheath at his belt, but his hand wasn't on it, so he wasn't looking for trouble.

So Alvin spoke up soft as could be. "If you're looking for food, the door's on the other side of the room."

Oh, the man's heart gave a jolt at that! And his first instinct was for his hand to fly to that knife -- he was quick at it, too, Alvin could see that it didn't much matter whether his hand was on the knife or not, he was always ready with that blade.

But in a moment the fellow got a hold of hisself, and Alvin could pretty much guess at his reasoning. It was a dark night, and as far as this fellow knew, Alvin couldn't see any better than him.

"You was snoring," said the man. "I was looking to jostle you to get you to roll over."

Alvin knew that was a flat lie. When Peggy had mentioned a snoring problem to him years ago, he studied out what made people snore and fixed his palate so it didn't make that noise any more. He had a rule about not using his knack to benefit himself, but he figured curing his snore was a gift to other people. He always slept through it.

Still, he'd let the lie ride. "Why, thank you," said Alvin. "I sleep pretty light, though, so all it takes is you sayin' 'roll over' and I'll do it. Or so my wife tells me."

And then, bold as brass, the fellow as much as confesses what he was doing. "You know, stranger, whatever you got in that sack, you hug it so close to you that somebody might get curious about what's so valuable."

"I've learned that folks get just as curious when I don't hug it close, and they feel a mite freer about groping in the dark to get a closer look."

The man chuckled. "So I reckon you ain't planning to tell me much about it."

"I always answer a well-mannered question," said Alvin.

"But since it ain't good manners to ask about what's in your sack," said the man, "I reckon you don't answer such questions at all."

"I'm glad to meet a man who knows good manners."

"Good manners and a knife that don't break off at the stem, that's what keeps me at peace with the world."

"Good manners has always been enough for me," said Alvin. "Though I admit I would have liked that knife better back when it was still a file."

With a bound the man was at the door, his knife drawn. "Who are you, and what do you know about me?"

"I don't know nothing about you, sir," said Alvin. "But I'm a blacksmith, and I know a file that's been made over into a knife. More like a sword, if you ask me."

"I haven't drawn my knife aboard this boat."

"I'm glad to hear it. But when I walked in on you asleep, it was still daylight enough to see the size and shape of the sheath you keep it in. Nobody makes a knife that thick at the haft, but it was right proportioned for a file."

"You can't tell something like that just from looking," said the man. "You heard something. Somebody's been talking."

"People are always talking, but not about you," said Alvin. "I know my trade, as I reckon you know yours. My name's Alvin."

"Alvin Smith, eh?"

"I count myself lucky to have a name. I'd lay good odds that you've got one too."

The man chuckled and put his knife away. "Jim Bowie."

"Don't sound like a trade name to me."

"It's a scotch word. Means light-haired."

"Your hair is dark."

"But I reckon the first Bowie was a blond Viking who liked what he saw while he was busy raping and pillaging in Scotland, and so he stayed."

"One of his children must have got that Viking spirit again and found his way across another sea."

"I'm a Viking through and through," said Bowie. "You guessed right about this knife. I was witness at a duel at a smithy just outside Natchez a few years ago. Things got out of hand when they both missed -- I reckon folks came to see blood and didn't want to be disappointed. One fellow managed to put a bullet through my leg, so I thought I was well out of it, until I saw Major Norris Wright setting on a boy half his size and half his age, and that riled me up. Riled me so bad that I clean forgot I was wounded and bleeding like a slaughtered pig. I went berserk and snatched up a blacksmith's file and stuck it clean through his heart."

"You got to be a strong man to do that."

"Oh, it's more than that. I didn't slip it between no ribs. I jammed it right through a rib. We Vikings get the strength of giants when we go berzerk."

"Am I right to guess that the knife you carry is that very same file?"

"A cutler in Philadelphia reshaped it for me."

"Did it by grinding, not forging," said Alvin.

"That's right."

"Your lucky knife."

"I ain't dead yet."

"Reckon that takes a lot of luck, if you got the habit of reaching over sleeping men to get at their poke."

The smile died on Bowie's face. "Can't help it if I'm curious."

"Oh, I know, I got me the same fault."

"So now it's your turn," said Bowie.

"My turn for what?"

"To tell your story."

"Me? Oh, all I got's a common skinning knife, but I've done my share of wandering in wild lands and it's come in handy."

"You know that's not what I'm asking."

"That's what I'm telling, though."

"I told you about my knife, so you tell me about your sack."

"You tell everybody about your knife," said Alvin, "which makes it so you don't have to use it so much. But I don't tell nobody about my sack."

"That just makes folks more curious," said Bowie. "And some folks might even get suspicious."

"From time to time that happens," said Alvin. He sat up and swung his legs over the side of his bunk and stood. He had already sized up this Bowie fellow and knew that he'd be at least four inches taller, with longer arms and the massive shoulders of a blacksmith. "But I smile so nice their suspicions just go away."

Bowie laughed out loud at that. "You're a big fellow, all right! And you ain't afeared of nobody."

"I'm afraid of lots of folks," said Alvin. "Especially a man can shove a file through a man's rib and ream out his heart."

Bowie nodded at that. "Well, now, ain't that peculiar. Lots of folks been afraid of me in my time. But the more scared they was, the less likely they was to admit it. You're the first one actually said he was afraid of me. So does that make you the most scared? Or the least?"

"Tell you what," said Alvin. "You keep your hands off my poke, and we'll never have to find out."

Bowie laughed again -- but his grin looked more like a wildcat snarling at its prey than like an actual smile. "I like you, Alvin Smith."

"I'm glad to hear it," said Alvin.

"I know a man who's looking for fellows like you."

So this Bowie was part of Austin's company. "If you're talking about Mr. Austin, he and I already agreed that he'll go his way and I'll go mine."

"Ah," said Bowie.

"Did you just join up with him in Thebes?"

"I'll tell you about my knife," said Bowie, "but I won't tell you about my business."

"I'll tell you mine," said Alvin. "My business right now is to get back to sleep and see if I can find the dream I was in before you decided to stop me snoring."

"Well, that's a good idea," said Bowie. "And since I haven't been to sleep at all yet tonight, on account of your snoring, I reckon I'll give it a go before the sun comes up."

Alvin lay back down and curled himself around his poke. His back was to Bowie, but of course he kept his doodlebug in him and knew every move he made. The man stood there watching Alvin for a long time, and from the way his heart was beating and the blood rushed around in him, Alvin could tell he was upset. Angry? Afraid? Hard to tell when you couldn't look at a man's face, and not so easy even then. But his heartfire blazed and Alvin figured the fellow was making some kind of decision about him.

Won't get to sleep very soon if he keeps himself all agitated like that, thought Alvin. So he reached inside the fellow and gradually calmed him down, got his heart beating slower, steadied his breathing. Most folks thought that their emotions caused their bodies to get all agitated, but it was the other way around, Alvin knew. The body leads, and the emotions follow.

In a couple of minutes Bowie was relaxed enough to yawn. And soon after, he was fast asleep. With his knife still strapped on, and his hand never far from it.

This Austin fellow had him some interesting friends.

Arthur Stuart was feeling way too cocky. But if you know you feel too cocky, and you compensate for it by being extra careful, then being cocky does you no harm, right? Except maybe it's your cockiness makes you feel like you're safer than you really are.

That's what Miz Peggy called "circular reasoning" and it wouldn't get him nowhere. Anywhere. One of them words. Whatever the rule was. Thinking about Miz Peggy always got him listening to the way he talked and finding fault with himself. Only what good would it do him to talk right? All he'd be is a half-Black man who somehow learned to talk like a gentleman -- a kind of trained monkey, that's how they'd see him. A dog walking on its hind legs. Not an actual gentleman.

Which was why he got so cocky, probably. Always wanting to prove something. Not to Alvin, really.

No, expecially to Alvin. Cause it was Alvin still treated him like a boy when he was a man now. Treated him like a son, but he was no man's son.

All this thinking was, of course, doing him no good at all, when his job was to pick up the foul-smelling slop bucket and make a slow and lazy job of it so's he'd have time to find out which of them spoke English or Spanish.

"Quien me compreende?" he whispered. "Who understands me?"

"Todos te compreendemos, pero calle la boca," whispered the third man. We all understand you, but shut your mouth. "Los blancos piensan que hay solo uno que hable un poco de ingles."

Boy howdy, he talked fast, with nothing like the accent the Cuban had. But still, when Arthur got the feel of a language in his mind, it wasn't that hard to sort it out. They all spoke Spanish, but they were pretending that only one of them spoke a bit of English.

"Quieren fugir de ser esclavos?" Do you want to escape from slavery?

"La unica puerta es la muerta." The only door is death.

"Al otro lado del rio," said Arthur, "hay rojos que son amigos nuestros." On the other side of the river there are Reds who are friends of ours.

"Sus amigos no son nuestros," answered the man. Your friends aren't ours.

Another man near enough to hear nodded in agreement. "Y ya no puedo nadar." And I can't swim anyway.

"Los blancos, que van a hacer?" What are the Whites going to do?

"Piensan en ser conquistadores." Clearly these men didn't think much of their masters' plans. "Los Mexicos van comer sus corazones." The Mexica will eat their hearts.

Another man chimed in. "Tu hablas como cubano." You talk like a Cuban.

"Soy americano," said Arthur Stuart. "Soy libre. Soy ..." He hadn't learned the Spanish for "citizen." "Soy igual." I'm equal. But not really, he thought. Still, I'm more equal than you.

Several of the Mexica Blacks sniffed at that. "Ya hay visto, tu dueño." All Arthur understood was "dueño," owner.

"Es amigo, no dueño." He's my friend, not my master.

Oh, they thought that was hilarious. But of course their laughter was silent, and a few of them glanced at the guard, who was dozing as he leaned against the wall.

"Me de promessa." Promise me. "Cuando el ferro quiebra, no se maten. No salguen sin ayuda." When the iron breaks, don't kill yourselves. Or maybe it meant don't get killed. Anyway, don't leave without help. Or that's what Arthur thought he was saying. They looked at him with total incomprehension.

"Voy quebrar el ferro," Arthur repeated.

One of them mockingly held out his hands. The chains made a noise. Several looked again at the guard.

"No con la mano," said Arthur. "Con la cabeza."

They looked at each other with obvious disappointment. Arthur knew what they were thinking -- this boy is crazy. Thinks he can break iron with his head. But he didn't know how to explain it any better.

"Mañana," he said.

They nodded wisely. Not a one of them believed him.

So much for the hours he'd spent learning Spanish. Though maybe the problem was that they just didn't know about makery and couldn't think of a man breaking iron with his mind.

Arthur Stuart knew he could do it. It was one of Alvin's earliest lessons, but it was only on this trip that Arthur had finally understood what Alvin meant. About getting inside the metal. All this time, Arthur had thought it was something he could do by straining real hard with his mind. But it wasn't like that at all. It was easy. Just a sort of turn of his mind. Kind of the way language worked for him. Getting the taste of the language on his tongue, and then trusting how it felt. Like knowing somehow that even though mano ended in o, it still needed la in front of it instead of el. He just knew how it ought to be.

Back in Carthage City, he gave two bits to a man selling sweet bread, and the man was trying to get away with not giving him change. Instead of yelling at him -- what good would that do, there on the levee, a half-Black boy yelling at a White man? -- Arthur just thought about the coin he'd been holding in his hand all morning, how warm it was, how right it felt in his own hand. It was like he understood the metal of it, the way he understood the music of language. And thinking of it warm like that, he could see in his mind that it was getting warmer.

He encouraged it, thought of it getting warmer and warmer, and all of a sudden the man cried out and started slapping at the pocket into which he'd dropped the quarter.

It was burning him.

He tried to get it out of his pocket, but it burned his fingers and finally he flung off his coat, flipped down his suspenders, and dropped his trousers, right in front of everybody. Tipped the coin out of his pocket onto the sidewalk, where it sizzled and made the wood start smoking.

Then all the man could think about was the sore place on his leg where the coin had burned him. Arthur Stuart walked up to him, all the time thinking the coin cool again. He reached down and picked it up off the sidewalk. "Reckon you oughta give me my change," he said.

"You get away from me, you Black devil," said the man. "You're a wizard, that's what you are. Cursing a man's coin, that's the same as thievin'!"

"That's awful funny, coming from a man who charged me two bits for a five-cent hunk of bread."

Several passersby chimed in.

"Trying to keep the boy's quarter, was you?"

"There's laws against that, even if the boy is Black."

"Stealin' from them as can't fight back."

"Pull up your trousers, fool."

A little later, Arthur Stuart got change for his quarter and tried to give the man his nickel, but he wouldn't let Arthur get near him.

Well, I tried, thought Arthur. I'm not a thief.

What I am is, I'm a maker.

No great shakes at it like Alvin, but dadgummit, I thought a quarter hot and it dang near burned its way out of the man's pocket.

If I can do that, then I can learn to do it all, that's what he thought, and that's why he was feeling cocky tonight. Because he'd been practicing every day on anything metal he could get his hands on. Wouldn't do no good to turn the iron hot enough to melt, of course -- these slaves wouldn't thank him if he burned their wrists and ankles up in the process of getting their chains off.

No, his project was to make the metal soft without getting it hot. That was a lot harder than hetting it up. Lots of times he'd caught himself straining again, trying to push softness onto the metal. But when he relaxed into it again and got the feel of the metal into his head like a song, he gradually began to get the knack of it again. Turned his own belt buckle so soft he could bend it into any shape he wanted. Though after a few minutes he realized the shape he wanted it in was like a belt buckle, since he still needed it to hold his pants up.

Brass was easier than iron, since it was softer in the first place. And it's not like Arthur Stuart was fast. He'd seen Alvin turn a gun barrel soft while a man was in the process of shooting it at him, that's how quick he was. But Arthur Stuart had to ponder on it first. Twenty-five slaves, each with an iron band at his ankle and another at his wrist. He had to make sure they all waited till the last one was free. If any of them bolted early, they'd all be caught.

Course, he could ask Alvin to help him. But he already had Alvin's answer. Leave 'em slaves, that's what Alvin had decided. But Arthur wouldn't do it. These men were in his hands. He was a maker now, after his own fashion, and it was up to him to decide for himself when it was right to act and right to let be. He couldn't do what Alvin did, healing folks and getting animals to do his bidding and turning water into glass. But he could soften iron, by damn, and so he'd set these men free.

Tomorrow night.

Next morning they passed from the Hio into the Mizzippy, and for the first time in years Alvin got a look at Tenskwa-Tawa's fog on the river.

It was like moving into a wall. Sunny sky, not a cloud, and when you looked ahead it really didn't look like much, just a little mist on the river. But all of a sudden you couldn't see more than a hundred yards ahead of you -- and that was only if you were headed up or down the river. If you kept going straight across to the right bank, it was like you went blind, you couldn't even see the front of your own boat.

It was the fence that Tenskwa Tawa had built to protect the Reds who moved west after the failure of Ta-Kumsaw's war. All the Reds who didn't want to live under White man's law, all the Reds who were done with war, they crossed over the water into the west, and then Tenskwa Tawa ... closed the door behind them.

Alvin had heard tales of the west from trappers who used to go there. They talked of mountains so sharp with stone, so rugged and high that they had snow on them clear into June. Places where the ground itself spat hot water fifty feet into the sky, or higher. Herds of buffalo so big they could pass by you all day and night, and next morning it still looked like there was just as many as yesterday. Grassland and desert, pine forest and lakes like jewels nestled among mountains so high that if you climbed to the top you ran out of air.

And all that was now Red land, where Whites would never go again. That's what this fog was all about.

Except for Alvin. He knew that if he wanted to, he could dispel that fog and cross over. Not only that, but he wouldn't be killed, neither. Tenskwa Tawa had said so, and there'd be no Red man who'd go against the Prophet's law.

A part of him wanted to put to shore, wait for the riverboat to move on, and then get him a canoe and paddle across the river and look for his old friend and teacher. It would be good to talk to him about all that was going on in the world. About the rumors of war coming, between the United States and the Crown Colonies -- or maybe between the free states and slave states within the U.S.A. About rumors of war with Spain to get control of the mouth of the Mizzippy, or war between the Crown Colonies and England.

And now this rumor of war with the Mexica. What would Tenskwa Tawa make of that? Maybe he had troubles of his own -- maybe he was working even now to make an alliance of Reds to head south and defend their lands against men who dragged their captives to the tops of their ziggurats and tore their hearts out to satisfy their god.

Anyway, that's the kind of thing going through Alvin's mind as he leaned on the rail on the right side of the boat -- the stabberd side, that was, though why boatmen should have different words for right and left made no sense to him. He was just standing there looking out into the fog and seeing no more than any other man, when he noticed something, not with his eyes, but with that inward vision that saw heartfires.

There was a couple of men out on the water, right out in the middle where they wouldn't be able to tell up from down. Spinning round and round, they were, and scared. It took only a moment to get the sense of it. Two men on a raft, only they didn't have drags under the raft and had it loaded front-heavy. Not boatmen, then. Had to be a homemade raft, and when their tiller broke they didn't know how to get the raft to keep its head straight downriver. At the mercy of the current, that's what, and no way of knowing what was happening five feet away.

Though it wasn't as if the Yazoo Queen was quiet. Still, fog had a way of damping down sounds. And even if they heard the riverboat, would they know what the sound was? To terrified men, it might sound like some kind of monster moving along the river.

Well, what could Alvin do about it? How could he claim to see what no one else could make out? And the flow of the river was too strong and complicated for him to get control of it, to steer the raft closer.

Time for some lying. Alvin turned around and shouted. "Did you hear that? Did you see them? Raft out of control on the river! Men on a raft, they were calling for help, spinning around out there!"

In no time the pilot and captain both were leaning over the rail of the pilot's deck. "I don't see a thing!" shouted the pilot.

"Not now," said Alvin. "But I saw 'em plain just a second ago, they're not far."

Captain Howard could see the drift of things and he didn't like it. "I'm not taking the Yazoo Queen any deeper into this fog than she already is! No sir! They'll fetch up on the bank farther downriver, it's no business of ours!"

"Law of the river!" shouted Alvin. "Men in distress!"

That gave the pilot pause. It was the law. You had to give aid.

"I don't see no men in distress!" shouted Captain Howard.

"So don't turn the big boat," said Alvin. "Let me take that little rowboat and I'll go fetch 'em."

Captain didn't like that either, but the pilot was a decent man and pretty soon Alvin was in the water with his hands on the oars.

But before he could fair get away, there was Arthur Stuart, leaping over the gap and sprawling into the little boat. "That was about as clumsy a move as I ever saw," said Alvin.

"I ain't gonna miss this," said Arthur Stuart.

There was another man at the rail, hailing him. "Don't be in such a hurry, Mr. Smith!" shouted Jim Bowie. "Two strong men is better than one on a job like this!" And then he, too, was leaping -- a fair job of it, too, considering he must be at least ten years older than Alvin and a good twenty years older than Arthur Stuart. But when he landed, there was no sprawl about it, and Alvin wondered what this man's knack was. He had supposed it was killing, but maybe the killing was just a sideline. The man fair to flew.

So there they were, each of them at a set of oars while Arthur Stuart sat in the stern and kept his eye peeled.

"How far are they?" he kept asking.

"The current might of took them farther out," said Alvin. "But they're there."

And when Arthur started looking downright skeptical, Alvin fixed him with such a glare that Arthur Stuart finally got it. "I think I see 'em," he said, giving Alvin's lie a boost.

"You ain't trying to cross this whole river and get us kilt by Reds," said Jim Bowie.

"No sir," said Alvin. "Got no such plan. I saw those boys, plain as day, and I don't want their death on my conscience."

"Well where are they now?"

Of course Alvin knew, and he was rowing toward them as best he could. Trouble was that Jim Bowie didn't know where they were, and he was rowing too, only not quite in the same direction as Alvin. And seeing as how both of them had their backs to where the raft was, Alvin couldn't even pretend to see them. He could only try to row stronger than Bowie in the direction he wanted to go.

Until Arthur Stuart rolled his eyes and said, "Would you two just stop pretending that anybody believes anybody, and row in the right direction?"

Bowie laughed. Alvin sighed.

"You didn't see nothin'," said Bowie. "Cause I was watching you looking out into the fog."

"Which is why you came along."

"Had to find out what you wanted to do with this boat."

"I want to rescue two lads on a flatboat that's spinning out of control on the current."

"You mean that's true?"

Alvin nodded, and Bowie laughed again. "Well I'm jiggered."

"That's between you and your jig," said Alvin. "More downstream, please."

"So what's your knack, man?" said Bowie. "Seeing through fog?"

"Looks like, don't it?"

"I think not," said Bowie. "I think there's a lot more to you than meets the eye."

Arthur Stuart looked Alvin's massive blacksmith's body up and down. "Is that possible?"

"And you're no slave," said Bowie.

There was no laugh when he said that. That was dangerous for any man to know.

"Am so," said Arthur Stuart.

"No slave would answer back like that, you poor fool," said Bowie. "You got such a mouth on you, there's no way you ever had a taste of the lash."

"Oh, it's a good idea for you to come with me on this trip," said Alvin.

"Don't worry," said Bowie. "I got secrets of my own. I can keep yours."

Can -- but will you? "Not much of a secret," said Alvin. "I'll just have to take him back north and come down later on another steamboat."

"Your arms and shoulders tell me you really are a smith," said Bowie. "But. Ain't no smith alive can look at a knife in its sheath and say it used to be a file."

"I'm good at what I do," said Alvin.

"Alvin Smith. You really ought to start traveling under another name."

"Why?"

"You're the smith what killed a couple of Finders a few years back."

"Finders who murdered my wife's mother."

"Oh, no jury would convict you," said Bowie. "No more than I got convicted for my killing. Looks to me like we got a lot in common."

"Less than you might think."

"Same Alvin Smith who absconded from his master with a particular item."

"A lie," said Alvin. "And he knows it."

"Oh, I'm sure it is. But so the story goes."

"You can't believe these tales."

"Oh, I know," said Bowie. "You aren't slacking off on your rowing, are you?"

"I'm not sure I want to overtake that raft while we're still having this conversation."

"I was just telling you, in my own quiet way, that I think I know what you got in that sack of yours. Some powerful knack you got, if the rumors are true."

"What do they say, that I can fly?"

"You can turn iron to gold, they say."

"Wouldn't that be nice," said Alvin.

"But you didn't deny it, did you?"

"I can't make iron into anything but horseshoes and hinges."

"You did it once, though, didn't you?"

"No sir," said Alvin. "I told you those stories were lies."

"I don't believe you."

"Then you're calling me a liar, sir," said Alvin.

"Oh, you're not going to take offense, are you? Because I have a way of winning all my duels."

Alvin didn't answer, and Bowie looked long and hard at Arthur Stuart. "Ah," said Bowie. "That's the way of it."

"What?" said Arthur Stuart.

"You ain't askeered of me," said Bowie, exaggerating his accent.

"Am so," said Arthur Stuart.

"You're scared of what I know, but you ain't a-scared of me taking down your 'master' in a duel."

"Terrified," said Arthur Stuart.

It was only a split second, but there were Bowie's oars a-dangling, and his knife out of its sheath and his body twisted around with his knife right at Alvin's throat.

Except that it wasn't a knife anymore. Just a handle.

The smile left Bowie's face pretty slow when he realized that his precious knife-made-from-a-file no longer had any iron in it.

"What did you do?" he asked.

"That's a pretty funny question," said Alvin, "coming from a man who meant to kill me."

"Meant to scare you is all," said Bowie. "You didn't have to do that to my knife."

"I got no knack for knowing a man's intentions," said Alvin. "Now turn around and row."

Bowie turned around and took hold of the oars again. "That knife was my luck."

"Then I reckon you just run out of it," said Alvin.

Arthur Stuart shook his head. "You oughta take more care about who you draw against, Mr. Bowie."

"You're the man we want," said Bowie. "That's all I wanted to say. Didn't have to wreck my knife."

"Next time you look to get a man on your team," said Alvin, "don't draw a knife on him."

"And don't threaten to tell his secrets," said Arthur Stuart.

And now, for the first time, Bowie looked more worried than peeved. "Now, I never said I knew your secrets. I just had some guesses, that's all."

"Well, Arthur Stuart, Mr. Bowie just noticed he's out here in the middle of the river, in the fog, on a dangerous rescue mission, with a couple of people whose secrets he threatened to tell."

"It's a position to give a man pause," said Arthur Stuart.

"I won't go out of this boat without a struggle," said Bowie.

"I don't plan to hurt you," said Alvin. "Because we're not alike, you and me. I killed a man once, in grief and rage, and I've regretted it ever since."

"Me too," said Bowie.

"It's the proudest moment of your life. You saved the weapon and called it your luck. We're not alike at all."

"I reckon not."

"And if I want you dead," said Alvin, "I don't have to throw you out of no boat."

Bowie nodded. And then took his hands off the oar. His hands began to flutter around his cheeks, around his mouth.

"Can't breathe, can you?" said Alvin. "Nobody's blocking you. Just do it, man. Breathe in, breathe out. You been doing it all your life."

It wasn't like Bowie was choking. He just couldn't get his body to do his will.

Alvin didn't keep it going till the man turned blue or nothing. Just long enough for Bowie to feel real helpless. And then he remembered how to breathe, just like that, and sucked in the air.

"So now that we've settled the fact that you're in no danger from me here on this boat," said Alvin, "let's rescue a couple of fellows got themselves on a homemade raft that got no drag."

And at that moment, the whiteness of the fog before them turned into a flatboat not five feet away. Another pull on the oars and they bumped it. Which was the first time the men on the raft had any idea that anybody was coming after them.

Arthur Stuart was already clambering to the bow of the boat, holding onto the stern rope and leaping onto the raft to make it fast.

"Lord be praised," said the smaller of the two men.

"You come at a right handy time," said the tall one, helping Arthur make the line fast. "Got us an unreliable raft here, and in this fog we wasn't even seeing that much of the countryside. A second-rate voyage by any reckoning."

Alvin laughed at that. "Glad to see you've kept your spirits up."

"Oh, we was both praying and singing hymns," said the lanky man.

"How tall are you?" said Arthur Stuart as the man loomed over him.

"About a head higher than my shoulders," said the man, "but not quite long enough for my suspenders."

The fellow had a way about him, right enough. You just couldn't help but like him.

Which made Alvin suspicious right off. If that was the man's knack, then he couldn't be trusted. And yet the most cussed thing about it was, even while you wasn't trusting him, you still had to like him.

"What are you, a lawyer?" asked Alvin.

By now they had maneuvered the boat to the front of the raft, ready to tug it along behind them as they rejoined the riverboat.

The man stood to his full height and then bowed, as awkward-looking a maneuver as Alvin had ever seen. He was all knees and elbows, angles everywhere, even his face, nothing soft about him, as bony a fellow as could be. No doubt about it, he was ugly. Eyebrows like an ape's, they protruded so far out over his eyes. And yet ... he wasn't bad to look at. Made you feel warm and welcome, when he smiled.

"Abraham Lincoln of Springfield, at your service, gentlemen," he said.

"And I'm Cuz Johnston of Springfield," said the other man.

"Cuz for 'Cousin,'" said Abraham. "Everybody calls him that."

"They do now," said Cuz.

"Whose cousin?" asked Arthur Stuart.

"Not mine," said Abraham. "But he looks like a cousin, don't he? He's the epitome of cousinhood, the quintessence of cousiniferosity. So when I started calling him Cuz, it was just stating the obvious."

"Actually, I'm his father's second wife's son by her first husband," said Cuz.

"Which makes us step-strangers," said Abraham. "In-law."

"I'm particularly grateful to you boys for pickin' us up," said Cuz, "on account of now old Abe here won't have to finish the most obnoxious tall tale I ever heard."

"It wasn't no tall tale," said old Abe. "I heard it from a man named Taleswapper. He had it in his book, and he didn't never put anything in it lessen it was true."

Old Abe -- who couldn't have been more than thirty -- was quick of eye. He saw the glance that passed between Alvin and Arthur Stuart.

"So you know him?" asked Abe.

"A truthful man, he is indeed," said Alvin. "What tale did he tell you?"

"Of a child born many years ago," said Abe. "A tragic tale of a brother who got kilt by a treetrunk carried downstream by a flood, which hit him while he was a-saving his mother, who was in a wagon in the middle of the stream, giving birth. But doomed as he was, he stayed alive long enough on that river that when the baby was born, it was the seventh son of a seventh son, and all the sons alive."

"A noble tale," said Alvin. "I've seen that one in his book my own self."

"And you believe it?"

"I do," said Alvin.

"I never said it wasn't true," said Cuz. "I just said it wasn't the tale a man wants to hear when he's spinning downstream on a flapdoodle flatboat in the midst of the Mizzippy mist."

Abe Lincoln ignored the near-poetic language of his companion. "So I was telling Cuz here that the river hadn't treated us half bad, compared to what a much smaller stream done to the folks in that story. And now here you are, saving us -- so the river's been downright kind to a couple of second-rate raftmakers."

"Made this one yourself, eh?" said Alvin.

"Tiller broke," said Abe.

"Didn't have no spare?" said Alvin.

"Didn't know I'd need one. But if we ever once fetched up on shore, I could have made another."

"Good with your hands?"

"Not really," said Abe. "But I'm willing to do it over till it's right."

Alvin laughed. "Well, time to do this raft over."

"I'd welcome it if you'd show me what we done wrong. I can't see a blame thing here that isn't good raftmaking."

"It's what's under the raft that's missing. Or rather, what ought to be there but ain't. You need a drag at the stern, to keep the back in back. And on top of that you've got it heavy-loaded in front, so it's bound to turn around any old way."

"Well I'm blamed," said Abe. "No doubt about it, I'm not cut out to be a boatman."

"Most folks aren't," said Alvin. "Except my friend Mr. Bowie here. He's just can't keep away from a boat, when he gets a chance to row."

Bowie gave a tight little smile and a nod to Abe and his companion. By now the raft was slogging along behind them in the water, and it was all Alvin and Bowie could do, to move it forward.

"Maybe," said Arthur Stuart, "the two of you could stand at the back of the raft so it didn't dig so deep in front and make it such a hard pull."

Embarrassed, Abe and Cuz did so at once. And in the thick fog of midstream, it made them mostly invisible and damped down any sound they made so that conversation was nigh impossible.

It took a good while to overtake the steamboat, but the pilot, being a good man, had taken it slow, despite Captain Howard's ire over time lost, and all of a sudden the fog thinned and the noise of the paddlewheels was right beside them as the Yazoo Queen loomed out of the fog.

"I'll be plucked and roasted," shouted Abe. "That's a right fine steamboat you got here."

"Tain't our'n," said Alvin.

Arthur Stuart noticed how little time it took Bowie to get himself up on deck and away from the boat, shrugging off all the hands clapping at his shoulder like he was a hero. Well, Arthur couldn't blame him. But it was a sure thing that however Alvin might have scared him out on the water, Bowie was still a danger to them both.

Once the dinghy was tied to the Yazoo Queen, and the raft lashed alongside as well, there was all kinds of chatter from passengers wanting to know obvious things like how they ever managed to find each other in the famous Mizzippy fog.

"It's like I said," Alvin told them. "They was right close, and even then, we still had to search."

Abe Lincoln heard it with a grin, and didn't say a word to contradict him, but he was no fool, Arthur Stuart could see that. He knew that the raft had been nowheres near the riverboat. He also knew that Alvin had steered straight for the Yazoo Queen as if he could see it.