[First appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1985]

The Folk of the Fringe (Phantasia Press/Tor, April 1989)

LaVon's book report was drivel, of course. Carpenter knew it would be from the moment he called on the boy. After Carpenter's warning last week, he knew LaVon would have a book report -- LaVon's father would never let the boy be suspended. But LaVon was too stubborn, too cocky, too much the leader of the other sixth-graders' constant rebellion against the authority to let Carpenter have a complete victory.

"I really, truly loved Little Men," said LaVon. "It just gave me goose bumps."

The class laughed. Excellent comic timing, Carpenter said silently. But the only place that comedy is useful here in the New Soil country is with the gypsy pageant wagons. That's what you're preparing yourself for, LaVon, a career as a wandering parasite who lives by sucking laughter out of weary farmers.

"Everybody nice in this book has a name that starts with a d. Demi is a sweet little boy who never does anything wrong. Daisy is so good that she could have seven children and still be a virgin."

He was pushing the limits now. A lot of people didn't like mention of sexual matters in the school, and if some pin-headed child decided to report this, the story could be twisted into something that could be used against Carpenter. Out here near the fringe, people were desperate for entertainment. A crusade to drive out a teacher for corrupting the morals of youth would be more fun than a traveling show, because everybody could feel righteous and safe when he was gone. Carpenter had seen it before. Not that he was afraid of it, the way most teachers were. He had a career no matter what. The university would take him back, eagerly; they thought he was crazy to go out and teach in the low schools. I'm safe, absolutely safe, he thought. They can't wreck my career. And I'm not going to get prissy about a perfectly good word like virgin.

"Dan looks like a big bad boy, but he has a heart of gold, even though he does say real bad words like devil sometimes." LaVon paused, waiting for Carpenter to react. So Carpenter did not react.

"The saddest thing is poor Nat, the street fiddler's boy. He tries hard to fit in, but he can never amount to anything in the book, because his name doesn't start with d."

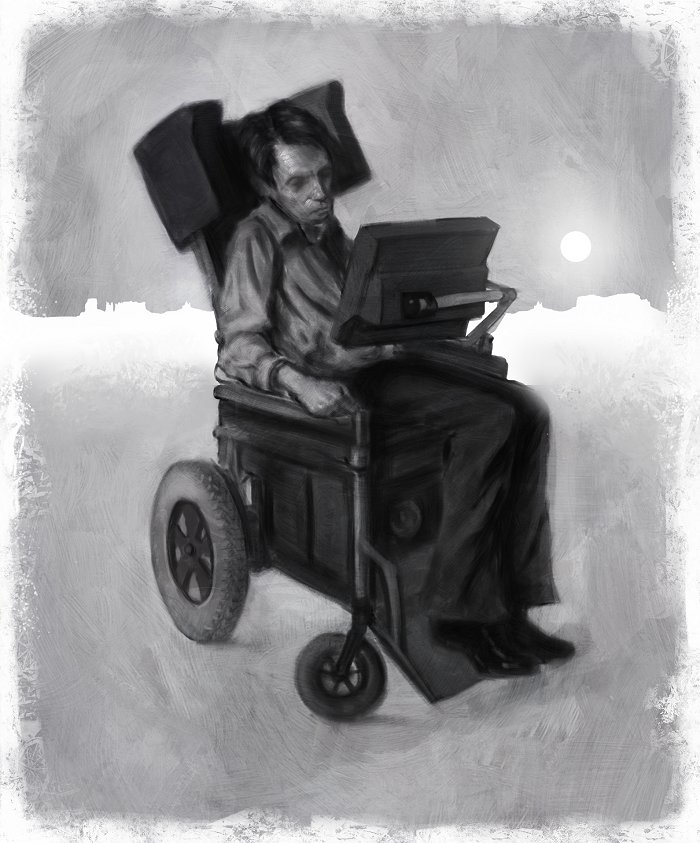

The end. LaVon put the single paper on Carpenter's desk, then went back to his seat. He walked with the careful elegance of a spider, each long leg moving as if it were unconnected to the rest of his body, so that even walking did not disturb the perfect calm. The boy rides on his body the way I ride in my wheelchair, thought Carpenter. Smooth, unmoved by his own motion. But he is graceful and beautiful, fifteen years old and already a master at winning the devotion of the weak-hearted children around him. He is the enemy, the torturer, the strong and beautiful man who must confirm his beauty by preying on the weak. I am not as weak as you think.

LaVon's book report was arrogant, far too short, and flagrantly rebellious. That much was deliberate, calculated to annoy Carpenter. Therefore Carpenter would not show the slightest trace of annoyance. The book report had also been clever, ironic, and funny. The boy, for all his mask of languor and stupidity, had brains. He was better than this farming town; he could do something that mattered in the world besides driving a tractor in endless contour patterns around the fields. But the way he always had the Fisher girl hanging on him, he'd no doubt have a baby and a wife and stay here forever. Become a big shot like his father, maybe, but never leave a mark in the world to show he'd been there. Tragic, stupid waste.

But don't show the anger. The children will misunderstand, they'll think I'm angry because of LaVon's rebelliousness, and it will only make this boy more of a hero in their eyes. Children choose their heroes with unerring stupidity. Fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old, all they know of life is cold and bookless classrooms interrupted now and then by a year or two of wrestling with this stony earth, always hating whatever adult it is who keeps them at their work, always adoring whatever fool gives them the illusion of being free. You children have no practice in surviving among the ruins of your own mistakes. We adults who knew the world before it fell, we feel the weight of the rubble on our backs.

They were waiting for Carpenter's answer. He reached out to the computer keyboard attached to his wheelchair. His hands struck like paws at the oversized keys. His fingers were too stupid for him to use them individually. They clenched when he tried to work them, tightened into a fist, a little hammer with which to strike, to break, to attack; he could not use them to grasp or even hold. Half the verbs of the world are impossible to me, he thought as he often thought. I learn them the way the blind learn words of seeing -- by rote, with no hope of ever knowing truly what they mean.

The speech synthesizer droned out the words he keyed. "Brilliant essay, Mr. Jensen. The irony was powerful, the savagery was refreshing. Unfortunately, it also revealed the poverty of your soul. Alcott's title was ironic, for she wanted to show that despite their small size, the boys in her book were great-hearted. You, however, despite your large size, are very small of heart indeed."

LaVon looked at him through heavy-lidded eyes. Hatred? Yes, it was there. Do hate me, child. Loathe me enough to show me that you can do anything I ask you to do. Then I'll own you, then I can get something decent out of you, and finally give you back to yourself as a human being who is worthy to be alive.

Carpenter pushed outward on both levers, and his wheelchair backed up. The day was nearly over, and tonight he knew some things would change, painfully, in the life of the town of Reefrock. And because in a way the arrests would be his fault, and because the imprisonment of a father would cause upheaval in some of these children's families, he felt it his duty to prepare them as best he could to understand why it had to happen, why, in the larger view, it was good. It was too much to expect that they would actually understand, today; but they might remember, might forgive him someday for what they would soon find out that he had done to them.

So he pawed at the keys again. "Economics," said the computer. "Since Mr. Jensen has made an end of literature for the day." A few more keys, and the lecture began. Carpenter entered all his lectures and stored them in memory, so that he could sit still as ice in his chair, making eye contact with each student in turn, daring them to be inattentive. There were advantages in letting a machine speak for him; he learned many years ago that it frightened people to have a mechanical voice speak his words, while his lips were motionless. It was monstrous, it made him seem dangerous and strange. Which he far preferred to the way he looked, weak as a worm, his skinny, twisted, palsied body rigid in his chair; his body looked strange, but pathetic. Only when the synthesizer spoke his acid words did he earn respect from the people who always, always looked downward at him.

"Here in the settlements just behind the fringe," his voice went on, "we do not have the luxury of a free economy. The rains sweep onto this ancient desert and find nothing here but a few plants growing in the sand. Thirty years ago, nothing lived here; even the lizards had to stay where there was something for insects to eat, where there was water to drink. Then the fires we lit put a curtain in the sky, and the ice moved south, and the rains that had always passed north of us now raked and scoured the desert. It was opportunity."

LaVon smirked as Kippie made a great show of dozing off. Carpenter keyed an interruption in the lecture. "Kippie, how well will you sleep if I send you home now for an afternoon nap?"

Kippie sat bolt upright, pretending terrible fear. But the pretense was also a pretense; he was afraid, and so to conceal it he pretended to be pretending to be afraid. Very complex, the inner life of children, thought Carpenter.

"Even as the old settlements were slowly drowned under the rising Great Salt Lake, your fathers and mothers began to move out into the desert, to reclaim it. But not alone. We can do nothing alone here. The fringers plant their grass. The grass feeds the herds and puts roots into the sand. The roots become humus, rich in nitrogen. In three years the fringe has a thin lace of soil across it. If at any point a fringer fails to plant, if at any point the soil is broken, then the rains eat channels under it, and tear away the fringe on either side, and eat back into farmland behind it. So every fringer is responsible to every other fringer, and to us. How would you feel about a fringer who failed?"

"The way I feel about a fringer who succeeds," said Pope. He was the youngest of the sixth-graders, only thirteen years old, and he sucked up to LaVon disgracefully.

Carpenter punched four codes. "And how is that?" asked Carpenter's metal voice.

Pope's courage fled. "Sorry."

Carpenter did not let go. "What is it you call fringers?" he asked. He looked from one child to the next, and they would not meet his gaze. Except LaVon.

"What do you call them?" he asked again.

"If I say it, I'll get kicked out of school," said LaVon. "You want me kicked out of school?"

"You accuse them of fornicating with cattle, yes?"

A few giggles.

"Yes sir," said LaVon. "We call them cow-fornicators, sir."

Carpenter keyed in his response while they laughed. When the room was silent, he played it back. "The bread you eat grows in the soil they created, and the manure of their cattle is the strength of your bodies. Without fringers you would be eking out a miserable life on the shores of the Mormon Sea, eating fish and drinking sage tea, and don't forget it." He set the volume of the synthesizer steadily lower during the speech, so that at the end they were straining to hear.

Then he resumed his lecture. "After the fringers came your mothers and fathers, planting crops in a scientifically planned order: two rows of apple trees, then six meters of wheat, then six meters of corn, then six meters of cucumbers, and so on, year after year, moving six more meters out, following the fringers, making more land, more food. If you didn't plant what you were told, and harvest it on the right day, and work shoulder to shoulder in the fields whenever the need came, then the plants would die, the rain would wash them away. What do you think of the farmer who does not do his labor or take his work turn?"

"Scum," one child said. And another: "He's a wallow, that what he is."

"If this land is to be truly alive, it must be planted in a careful plan for eighteen years. Only then will your family have the luxury of deciding what crop to plant. Only then will you be able to be lazy if you want to, or work extra hard and profit from it. Then some of you can get rich, and others can become poor. But now, today, we do everything together, equally, and so we share equally in the rewards of our work."

LaVon murmured something.

"Yes, LaVon?" asked Carpenter. He made the computer speak very loudly. It startled the children.

"Nothing," said LaVon.

"You said: Except teachers."

"What if I did?"

"You are correct," said Carpenter. "Teachers do not plow and plant in the fields with your parents. Teachers are given much more barren soil to work in, and most of the time the few seeds we plant are washed away with the first spring shower. You are living proof of the futility of our labor. But we try, Mr. Jensen, foolish as the effort is. May we continue?"

LaVon nodded. His face was flushed. Carpenter was satisfied. The boy was not hopeless -- he could still feel shame at having attacked a man's livelihood.

"There are some among us," said the lecture, "who believe they should benefit more than others from the work of all. These are the ones who steal from the common storehouse and sell the crops that were raised by everyone's labor. The black market pays high prices for the stolen grain, and the thieves get rich. When they get rich enough, they move away from the fringe, back to the cities of the high valleys. Their wives will wear fine clothing, their sons will have watches, their daughters will own land and marry well. And in the meantime, their friends andneighbors, who trusted them, will have nothing, will stay on the fringe, growing the food that feeds the thieves. Tell me, what do you think of a black marketeer?"

He watched their faces. Yes, they knew. He could see how they glanced surreptitiously at Dick's new shoes, at Kippie's wristwatch. At Yutonna's new city-bought house. At LaVon's jeans. They knew, but out of fear they had said nothing. Or perhaps it wasn't fear. Perhaps it was the hope that their own father would be clever enough to steal from the harvest, so they could move away instead of earning out their eighteen years.

"Some people think these thieves are clever. But I tell you they are exactly like the mobbers of the plains. They are the enemies of civilization."

"This is civilization?" asked LaVon.

"Yes." Carpenter keyed an answer. "We live in peace here, and you know that today's work brings tomorrow's bread. Out on the prairie, they don't know that. Tomorrow a mobber will be eating their bread, if they haven't been killed. There's no trust in the world, except here. And the black marketeers feed on trust. Their neighbors' trust. When they've eaten it all, children, what will you live on then?"

They didn't understand, of course. When it was story problems about one truck approaching another truck at sixty kleeters and it takes an hour to meet, how far away were they? -- the children could handle that, could figure it out laboriously with pencil and paper and prayers and curses. But the questions that mattered sailed past them like little dust devils, noticed but untouched by their feeble, self-centered little minds.

He tormented them with a pop quiz on history and thirty spelling words for their homework, then sent them out the door.

LaVon did not leave. He stood by the door, closed it, spoke. "It was a stupid book," he said.

Carpenter clicked the keyboard. "That explains why you wrote a stupid book report."

"It wasn't stupid. It was funny. I read the damn book, didn't I?"

"And I gave you a B."

LaVon was silent a moment, then said, "Do me no favors."

"I never will."

"And shut up with the goddamn machine voice. You can make a voice yourself. My cousin's got palsy and she howls to the moon."

"You may leave now, Mr. Jensen."

"I'm gonna hear you talk in your natural voice someday, Mr. Machine."

"You had better go home now, Mr. Jensen."

LaVon opened the door to leave, then turned abruptly and strode the dozen steps to the head of the class. His legs now were tight and powerful as horses' legs, and his arms were light and strong. Carpenter watched him and felt the same old fear rise within him. If God was going to let him be born like this, he could at least keep him safe from the torturers.

"What do you want, Mr. Jensen?" But before the computer had finished speaking Carpenter's words, LaVon reached out and took Carpenter's wrists, held them tightly. Carpenter did not try to resist; if he did, he might go tight and twist around on the chair like a slug on a hot shovel. That would be more humiliation then he could bear, to have this boy see him writhe. His hands hung limp from LaVon's powerful fists.

"You just mind your business," LaVon said. "You only been here two years, you don't know nothin, you understand? You don't see nothin, you don't say nothin, you understand?"

So it wasn't the book report at all. LaVon had actually understood the lecture about civilization and the black market. And knew that it was LaVon's own father, more than anyone else in town, who was guilty. Nephi Delos Jensen, bigshot foreman of Reefrock Farms. Have the marshals already taken your father? Best get home and see.

"Do you understand me?"

But Carpenter would not speak. Not without his computer. This boy would never hear how Carpenter's own voice sounded, the whining, baying sound, like a dog trying to curl its tongue into human speech. You'll never hear my voice, boy.

"Just try to expel me for this, Mr. Carpenter. I'll say it never happened. I'll say you had it in for me."

Then he let go of Carpenter's hands and stalked from the room. Only then did Carpenter's legs go rigid, lifting him on the chair so that only the computer over his lap kept him from sliding off. His arms pressed outward, his neck twisted, his jaw opened wide. It was what his body did with fear and rage; it was why he did his best never to feel those emotions. Or any others, for that matter. Dispassionate, that's what he was. He lived the life of the mind, since the life of the body was beyond him. He stretched across his wheelchair like a mocking crucifix, hating his body and pretending that he was merely waiting for it to calm, to relax.

And it did, of course. As soon as he had control of his hands again, he took the computer out of speech mode and called up the data he had sent to Zarahemla yesterday morning. The crop estimates for three years, and the final weight of the harvested wheat and corn, cukes and berries, apples and beans. For the first two years, the estimates were within two percent of the final total. The third year, the estimates were higher, but the harvest stayed the same. It was suspicious. Then the bishop's accounting records. It was a sick community. When the bishop was also seduced into this sort of thing, it meant the rottenness touched every corner of village life. Reefrock Farms looked no different from the hundred other villages just this side of the fringe, but it was diseased. Did Kippie know that even his father was in on the black marketeering? If you couldn't trust the bishop, who was left?

The words of his own thoughts tasted sour in his mouth. Diseased. They aren't so sick, Carpenter, he told himself. Civilization has always had its parasites, and survived. But it survived because it rooted them out from time to time, cast them away and cleansed the body. Yet they made heroes out of the thieves and despised those who reported them. There's no thanks in what I've done. It isn't love I'm earning. It isn't love I feel. Can I pretend that I'm not just a sick and twisted body taking vengeance on those healthy enough to have families, healthy enough to want to get every possible advantage for them?

He pushed the levers inward and the chair rolled forward. He skillfully maneuvered between the chairs, but it still took nearly a full minute to get to the door. I'm a snail. A worm living in a metal carapace, a water snail creeping along the edge of the aquarium glass, trying to keep it clean from the filth of the fish. I'm the loathsome one; they're the golden ones that shine in the sparkling water. They're the ones whose death is mourned. But without me they'd die. I'm as responsible for their beauty as they are. More, because I work to sustain it, and they simply -- are.

It came out this way whenever he tried to reason out an excuse for his own life. He rolled down the corridor to the front door of the school. He knew, intellectually, that his work in crop rotation and timing had been the key to opening up the vast New Soil Lands here in the eastern Utah desert. Hadn't they invented a civilian medal for him, and then, for good measure, given him the same medal they gave to the freedom riders who went out and brought immigrant trains safely into the mountains? I was a hero, they said, this worm in his wheelchair house. But Governor Monson had looked at him with those distant, pitying eyes. He, too, saw the worm; Carpenter might be a hero, but he was still Carpenter.

They had built a concrete ramp for his chair after the second time the students knocked over the wooden ramp and forced him to summon help through the computer airlink network. He remembered sitting on the lip of the porch, looking out toward the cabins of the village. If anyone saw him, then they consented to his imprisonment, because they didn't come to help him. But Carpenter understood. Fear of the strange, the unknown. It wasn't comfortable for them, to be near Mr. Carpenter with the mechanical voice and the electric rolling chair. He understood, he really did, he was human too, wasn't he? He even agreed with them. Pretend Carpenter isn't there, and maybe he'll go away.

The helicopter came as he rolled out onto the asphalt of the street. It landed in the Circle, between the storehouse and the chapel. Four marshals came out of the gash in its side and spread out through the town.

It happened that Carpenter was rolling in front of Bishop Anderson's house when the marshal knocked down the door. He hadn't expected them to make the arrests while he was still going down the street. His first impulse was to speed up, to get away from the street. He didn't want to see. He liked Bishop Anderson. Used to, anyway. He didn't wish him ill. If the bishop had kept his hands out of the harvest, if he hadn't betrayed his trust, he wouldn't have been afraid to hear the knock on the door and see the badge in the marshal's hand.

Carpenter could hear Sister Anderson crying as they led her husband away. Was Kippie there, watching? Did he notice Mr. Carpenter passing by on the road? Carpenter knew what it would cost these families. Not just the shame, though it would be intense. Far worse would be the loss of their father for years, the extra labor for the children. To break up a family was a terrible thing to do, for the innocent would pay as great a cost as their guilty father, and it wasn't fair, for they had done no wrong. But it was the stern necessity, if civilization was to survive.

Carpenter slowed down his wheelchair, forcing himself to hear the weeping from the bishop's house, to let them look at him with hatred if they knew what he had done. And they would know: he had specifically refused to be anonymous. If I can inflict stern necessity on them, then I must not run from the consequences of my own actions. I will bear what I must bear, as well -- the grief, the resentment, and the rage of the few families I have harmed for the sake of all the rest.

The helicopter had taken off again before Carpenter's chair took him home. It sputtered overhead and disappeared into the low clouds. Rain again tomorrow, of course. Three days dry, three days wet, it had been the weather pattern all spring. The rain would come pounding tonight. Four hours till dark. Maybe the rain wouldn't come until dark.

He looked up from his book. He had heard footsteps outside his house. And whispers. He rolled to the window and looked out. The sky was a little darker. The computer said it was four-thirty. The wind was coming up. But the sounds he heard hadn't been the wind. It was three-thirty when the marshals came. Four-thirty now, and footsteps and whispers outside his house. He felt the stiffening in his arms and legs. Wait, he told himself. There's nothing to fear. Relax. Quiet. Yes. His body eased. His heart pounded, but it was slowing down.

The door crashed down. He was rigid at once. He couldn't even bring his hands down to touch the levers so he could turn to see who it was. He just spread there helplessly in his chair as the heavy footsteps came closer.

"There he is." The voice was Kippie's.

Hands seized his arms, pulled on him; the chair rocked as they tugged him to one side. He could not relax. "Son of a bitch is stiff as a statue." Pope's voice. Get out of here, little boy, said Carpenter, you're in something too deep for you, too deep for any of you. But of course they did not hear him, since his fingers couldn't reach the keyboard where he kept his voice.

"Maybe this is what he does when he isn't at school. Just sits here and makes statues at the window." Kippie laughed.

"He's scared stiff, that's what he is."

"Just bring him out, and fast." LaVon's voice carried authority.

They tried to lift him out of the chair, but his body was too rigid; they hurt him, though, trying, for his thighs pressed up against the computer with cruel force, and they wrung at his arms.

"Just carry the whole chair," said LaVon.

They picked up the chair and pulled him toward the door. His arms smacked against the corners and the doorframe. "It's like he's dead or something," said Kippie. "He don't say nothin."

He was shouting at them in his mind, however. What are you doing here? Getting some sort of vengeance? Do you think punishing me will bring your fathers back, you fools?

They pulled and pushed the chair into the van they had parked in front. The bishop's van -- Kippie wouldn't have the use of that much longer. How much of the stolen grain was carried in here?

"He's going to roll around back here," said Kippie.

"Tip him over," said LaVon.

Carpenter felt the chair fly under him; by chance he landed in such a way that his left arm was not caught behind the chair. It would have broken then. As it was, the impact with the floor bent his arm forcibly against the strength of his spasmed muscles; he felt something tear, and his throat made a sound in spite of his effort to bear it silently.

"Did you hear that?" said Pope. "He's got a voice."

"Not for much longer," said LaVon.

For the first time, Carpenter realized that it wasn't just pain that he had to fear. Now, only an hour after their fathers had been taken, long before time could cool their rage, these boys had murder in their hearts.

The road was smooth enough in town, but soon it became rough and painful. From that, Carpenter knew they were headed toward the fringe. He could feel the cold metal of the van's corrugated floor against his face; the pain in his arm was settling down to a steady throb. Relax, quiet, calm, he told himself. How many times in your life have you wished to die? Death means nothing to you, fool, you decided that years ago, death is nothing but a release from this corpse. So, what are you afraid of? Calm, quiet. His arms bent, his legs relaxed.

"He's getting soft again," reported Pope. From the front of the van Kippie guffawed. "Little and squirmy. Mr. Bug. We always call you that, you hear me, Mr. Bug? There was always two of you. Mr. Machine and Mr. Bug. Mr. Machine was mean and tough and smart, but Mr. Bug was weak and squishy and gross, with wiggly legs. Made us want to puke, looking at Mr. Bug."

I've been tormented by master torturers in my childhood, Pope Griffith. You are only a pathetic echo of their talent. Carpenter's words were silent, until his hands found the keys. His left hand was almost too weak to use, after the fall, so he coded the words clumsily with his right hand alone. "If I disappear the day of your father's arrest, Mr. Griffith, don't you think they'll guess who took me?"

"Keep his hands away from the keys!" shouted LaVon. "Don't let him touch the computer."

Almost immediately, the van lurched and took a savage bounce as it left the roadway. Now it was clattering over rough, unfinished ground. Carpenter's head banged against the metal floor, again and again. The pain of it made him go rigid; fortunately, spasms always carried his head upward to the right, so that his rigidity kept him from having his head beaten to unconsciousness.

Soon the bouncing stopped. The engine died. Carpenter could hear the wind whispering over the open desert land. They were beyond the fields and orchards, out past the grassland of the fringe. The van doors opened. LaVon and Kippie reached in and pulled him out, chair and all. They dragged the chair to the top of a wash. There was no water in it yet.

"Let's just throw him down," said Kippie. "Break his spastic little neck." Carpenter had not guessed that anger could burn so hot in these languid, mocking boys.

But LaVon showed no fire. He was cold and smooth as snow. "I don't want to kill him yet. I want to hear him talk first."

Carpenter reached out to code an answer. LaVon slapped his hands away, gripped the computer, braced a foot on the wheelchair, and tore the computer off its mounting. He threw it across the arroyo; it smacked against the far side and tumbled down into the dry wash. Probably it wasn't damaged, but it wasn't the computer Carpenter was frightened for. Until now Carpenter could cling to a hope that they just meant to frighten him. But it was unthinkable to treat precious electronic equipment that way, not if civilization still had any hold on LaVon.

"With your voice, Mr. Carpenter. Not the machine, your own voice."

Not for you, Mr. Jensen. I don't humiliate myself for you.

"Come on," said Pope. "You know what we said. We just take him down into the wash and leave him there."

"We'll send him down the quick way," said Kippie. He shoved at the wheelchair, teetering it toward the brink.

"We'll take him down!" shouted Pope. "We aren't going to kill him! You promised!"

"Lot of difference it makes," said Kippie. "As soon as it rains in the mountains, this sucker's gonna fill up with water and give him the swim of his life."

"We won't kill him," insisted Pope.

"Come on," said LaVon. "Let's get him down into the wash."

Carpenter concentrated on not going rigid as they wrestled the chair down the slope. The walls of the wash weren't sheer, but they were steep enough that the climb down wasn't easy. Carpenter tried to concentrate on mathematics problems so he wouldn't panic and writhe for them again. Finally the chair came to rest at the bottom of the wash.

"You think you can come here and decide who's good and who's bad, right?" said LaVon. "You think you can sit on your little throne and decide whose father's going to jail, is that it?"

Carpenter's hands rested on the twisted mountings that used to hold his computer. He felt naked, defenseless without his stinging, frightening voice to whip them into line. LaVon was smart to take away his voice. LaVon knew what Carpenter could do with words.

"Everybody does it," said Kippie. "You're the only one who doesn't black the harvest, and that's only because you can't."

"It's easy to be straight when you can't get anything on the side anyway," said Pope.

Nothing's easy, Mr. Griffith. Not even virtue.

"My father's a good man!" shouted Kippie. "He's the bishop, for Christ's sake! And you sent him to jail!"

"If he ain't shot," said Pope.

"They don't shoot you for blackmailing anymore," said LaVon. "That was in the old days."

The old days. Only five years ago. But those were the old days for these children. Children are innocent in the eyes of God, Carpenter reminded himself. He tried to believe that these boys didn't know what they were doing to him.

Kippie and Pope started up the side of the wash. "Come on," said Pope. "Come on, LaVon."

"Minute," said LaVon. He leaned close to Carpenter and spoke softly, intensely, his breath hot and foul, his spittle like sparks from a cookfire on Carpenter's face. "Just ask me," he said. "Just open your mouth and beg me, little man, and I'll carry you back up to the van. They'll let you live if I tell them to, you know that."

He knew it. But he also knew that LaVon would never tell them to spare his life.

"Beg me, Mr. Carpenter. Ask me please to let you live, and you'll live. Look. I'll even save your talkbox for you." He scooped up the computer from the sandy bottom and heaved it up out of the wash. It sailed over Kippie's head just as he was emerging from the arroyo.

"What the hell was that, you trying to kill me?"

LaVon whispered again. "You know how many times you made me crawl? And now I gotta crawl forever, my father's a jailbird thanks to you, I got little brothers and sisters, even if you hate me, what've you got against them, huh?"

A drop of rain struck Carpenter in the face. There were a few more drops.

"Feel that?" said LaVon. "The rain in the mountains makes this wash flood every time. You crawl for me, Carpenter, and I'll take you up."

Carpenter didn't feel particularly brave as he kept his mouth shut and made no sound. If he actually believed LaVon might keep his promise, he would swallow his pride and beg. But LaVon was lying. He couldn't afford to save Carpenter's life now, even if he wanted to. It had gone too far, the consequences would be too great. Carpenter had to die, accidentally drowned, no witness, such a sad thing, such a great man, and no one the wiser about the three boys who carried him to his dying place.

If he begged and whined in his hound voice, his cat voice, his bestial monster voice, then Lavon would smirk at him in triumph and whisper, "Sucker." Carpenter knew the boy too well. Tomorrow LaVon would have second thoughts, of course, but right now there'd be no softening. He only wanted to watch Carpenter twist like a worm and bay like a hound before he died. It was a victory, then, to keep silence. Let him remember me in his nightmares of guilt, let him remember I had courage enough not to whimper.

LaVon spat at him; the spittle struck him in the chest. "I can't even get it in your ugly little worm face," he said. Then he shoved the wheelchair and scrambled up the bank of the wash.

For a moment the chair hung in balance; then it tipped over. This time Carpenter relaxed during the fall and rolled out of the chair without further injury. His back was to the side of the wash they had climbed; he couldn't see if they were watching him or not. So he held still, except for a slight twitching of his hurt left arm. After a while the van drove away.

Only then did he begin to reach out his arms and paw at the mud of the arroyo bottom. His legs were completely useless, dragging behind him. But he was not totally helpless without his chair. He could control his arms, and by reaching them out and then pulling his body onto his elbows he could make good progress across the sand. How did they think he got from his wheelchair to bed, or to the toilet? Hadn't they seen him use his hands and arms? Of course they saw, but they assumed that because arms were weak, they were useless.

Then he got to the arroyo wall and realized that they were useless. As soon as there was any slope to climb, his left arm began to hurt badly. And the bank was steep. Without being able to use his fingers to clutch at one of the sagebrushes or tree starts, there was no hope he could climb out.

The lightning was flashing in the distance, and he could hear the thunder. The rain here was a steady plick plick plick on the sand, a tiny slapping sound on the few leaves. It would already be raining heavily in the mountains. Soon the water would be here.

He dragged himself another meter up the slope despite the pain. The sand scraped his elbows as he dug with them to pull himself along. The rain fell steadily now, many large drops, but still not a downpour. It was little comfort to Carpenter. Water was beginning to dribble down the sides of the wash and form puddles in the streambed.

With bitter humor he imagined himself telling Dean Wintz, On second thought, I don't want to go out and teach sixth grade. I'll just go right on teaching them here, when they come off the farm. Just the few who want to learn something beyond sixth grade, who want a university education. The ones who love books and numbers and languages, the ones who understand civilization and want to keep it alive. Give me children who want to learn, instead of these poor sandscrapers who only go to school because the law commands that six years out of their first fifteen years have to be spent as captives in the prison of learning.

Why do the fire-eaters go out searching for the old missile sites and risk their lives disarming them? To preserve civilization. Why do the freedom riders leave their safe home and go out to bring the frightened, lonely refugees in to the safety of the mountains? To preserve civilization.

And why had Timothy Carpenter informed the marshals about the black marketeering he had discovered in Reefrock Farms? Was it, truly, to preserve civilization?

Yes, he insisted to himself.

The water was flowing now along the bottom of the wash. His feet were near the flow. He painfully pulled himself up another meter. He had to keep his body pointed straight toward the side of the wash, or he would not be able to stop himself from rolling to one side or the other. He found that by kicking his legs in his spastic, uncontrolled fashion, he could root the toes of his shoes into the sand just enough that he could take some pressure off his arms, just for a moment.

No, he told himself. It was not just to preserve civilization. It was because of the swaggering way their children walked, in their stolen clothing, with their full bellies and healthy skin and hair, cocky as only security can make a child feel. Enough and to spare, that's what they had, while the poor suckers around them worried whether there'd be food enough for the winter, and if their mother was getting enough so the nursing baby wouldn't lack, and whether their shoes could last another summer. The thieves could take a wagon up the long road to Price or even to Zarahemla, the shining city on the Mormon Sea, while the children of honest men never saw anything but the dust and sand and ruddy mountains of the fringe.

Carpenter hated them for that, for all the differences in the world, for the children who had legs and walked nowhere that mattered, for the children who had voices and used them to speak stupidity, who had deft and clever fingers and used them to frighten and compel the weak. For all the inequities in the world he hated them and wanted them to pay for it. They couldn't go to jail for having obedient arms and legs and tongues, but they could damn well go for stealing the hard-earned harvest of trusting men and women. Whatever his own motives might be, that was reason enough to call it justice.

The water was rising many centimeters every minute. The current was tugging at his feet now. He released his elbows to reach them up for another, higher purchase on the bank, but no sooner had he reached out his arms than he slid downward and the current pulled harder at him. It took great effort just to return to where he started, and his left arm was on fire with the tearing muscles. Still, it was life, wasn't it? His left elbow rooted him in place while he reached with his right arm and climbed higher still, and again higher. He even tried to use his fingers to cling to the soil, to a branch, to a rock, but his fists stayed closed and hammered uselessly against the ground.

Am I vengeful, bitter, spiteful? Maybe I am. But whatever my motive was, they were thieves, and had no business remaining among the people they betrayed. It was hard on the children, of course, cruelly hard on them, to have their father stripped away from them by the authorities. But how much worse would it be for the fathers to stay, and the children to learn that trust was for the stupid and honor for the weak? What kind of people would we be then, if the children could do their numbers and letters but couldn't hold someone else's plate and leave the food on it untouched?

The water was up to his waist. The current was rocking him slightly, pulling him downstream. His legs were floating behind him now, and water was trickling down the bank, making the earth looser under his elbows. So the children wanted him dead now, in their fury. He would die in a good cause, wouldn't he?

With the water rising faster, the current swifter, he decided that martyrdom was not all it was cracked up to be. Nor was life, when he came right down to it, something to be given up lightly because of a few inconveniences. He managed to squirm up a few more centimeters, but now a shelf of earth blocked him. Someone with hands could have reached over it easily and grabbed hold of the sagebrush just above it.

He clenched his mouth tight and lifted his arm up onto the shelf of dirt. He tried to scrape some purchase for his forearm, but the soil was slick. When he tried to place some weight on the arm, he slid down again.

This was it, this was his death, he could feel it, and in the sudden rush of fear his body went rigid. Almost at once his feet caught on the rocky bed of the river, and stopped him from sliding farther. Spastic, his legs were of some use to him. He swung his right arm up, scraped his fist on the sagebrush stem, trying to pry his clenched fingers open.

And, with agonizing effort, he did it. All but the smallest finger opened enough to hook the stem. Now the clenching was some help to him. He used his left arm mercilessly, ignoring the pain, to pull him up a little farther, onto the shelf; his feet were still in the water, but his waist wasn't, and the current wasn't strong against him now.

It was a victory, but not much of one. The water wasn't even a meter deep yet, and the current wasn't yet strong enough to have carried away his wheelchair. But it was enough to kill him, if he hadn't come this far. Still, what was he really accomplishing? In storms like this, the water came up near the top; he'd have been dead for an hour before the water began to come down again.

He could hear, in the distance, a vehicle approaching on the road. Had they come back to watch him die? They couldn't be that stupid. How far was this wash from the highway? Not far -- they hadn't driven that long on the rough ground to get here. But it meant nothing. No one would see him, or even the computer that lay among the tumbleweeds and sagebrush at the arroyo's edge.

They might hear him. It was possible. If their window was open -- in a rainstorm? If their engine was quiet -- but loud enough that he could hear them? Impossible, impossible. And it might be the boys again, come to hear him scream and whine for life; I'm not going to cry out now, after so many years of silence --

But the will to live, he discovered, was stronger than shame; his voice came unbidden to his throat. His lips and tongue and teeth that in childhood had so painstakingly practiced words that only his family could ever understand now formed a word again: "Help!" It was a difficult word; it almost closed his mouth, it made him too quiet to hear. So at last he simply howled, saying nothing except the terrible sound of his voice.

The brake squealed, long and loud, and the vehicle rattled to a stop. The engine died. Carpenter howled. Car doors slammed.

"I tell you it's just a dog somewhere, somebody's old dog --"

Carpenter howled again.

"Dog or not, it's alive, isn't it?"

They ran along the edge of the arroyo, and someone saw him.

"A little kid!"

"What's he doing down there!"

"Come on, kid, you can climb up from there!"

I nearly killed myself climbing this far, you fool, if I could climb, don't you think I would have? Help me! He cried out again.

"It's not a little boy. He's got a beard --"

"Come on, hold on, we're coming down!"

"There's a wheelchair in the water --"

"He must be a cripple."

There were several voices, some of them women, but it was two strong men who reached him, splashing their feet in the water. They hooked him under the arms and carried him to the top.

"Can you stand up? Are you all right? Can you stand?"

Carpenter strained to squeeze out the word: "No."

The older woman took command. "He's got palsy, as any fool can see. Go back down there and get his wheelchair, Tom, no sense in making him wait till they can get him another one, go on down! It's not that bad down there, the flood isn't here yet!" Her voice was crisp and clear, perfect speech, almost foreign it was so precise. She and the young woman carried him to the truck. It was a big old flatbed truck from the old days, and on its back was a canvas-covered heap of odd shapes. On the canvas Carpenter read the words SWEETWATER'S MIRACLE PAGEANT. Traveling show people, then, racing for town to get out of the rain, and through some miracle they had heard his call.

"Your poor arms," said the young woman, wiping off grit and sand that had sliced his elbow. "Did you climb that far out of there with just your arms."

The young man came out of the arroyo muddy and cursing, but they had the wheelchair. They tied it quickly to the back of the truck; one of the men found the computer, too, and took it inside the cab. It was designed to be rugged, and to Carpenter's relief it still worked.

"Thank you," said his mechanical voice.

"I told them I heard something and they said I was crazy," said the old woman. "You live in Reefrock?"

"Yes," said his voice.

"Amazing what those old machines can still do, even after being dumped there in the rain," said the old woman. "Well, you came close to death, there, but you're all right, it's the best we can ask for. We'll take you to the doctor."

"Just take me home, please."

So they did, but insisted on helping him bathe and fixing him dinner. The rain was coming down in sheets when they were done. "All I have is a floor," he said, "but you can stay."

"Better than trying to pitch tents in this." So they stayed the night.

Carpenter's arms ached too badly for him to sleep, even though he was exhausted. He lay awake thinking of the current pulling him, imagining what would have happened to him, how far he might have gone downstream before drowning, where his body might have ended up. Caught in a snag somewhere, dangling on some branch or rock as the water went down and left his slack body to dry in the sun. Far out in the desert somewhere, maybe. Or perhaps the floodwater might have carried him all the way to the Colorado and tumbled him head over heels down the rapids, through canyons, past the ruins of the old dams, and finally into the Gulf of California. He'd pass through Navaho territory then, and the Hopi Protectorate, and into areas that Chihuahua claimed and threatened to go to war to keep. He'd see more of the world than he had seen in his life.

I saw more of the world tonight, he thought, than I ever thought to see. I saw death and how much I feared it.

And he looked unto himself, wondering how much he had changed.

Late in the morning, when he finally awoke, the pageant people were gone. They had a show, of course, and had to do some kind of parade to let people know. School would let out early so they could put on a show without having to waste power on lights. There'd be no school this afternoon. But what about his morning classes? There must have been some question when he didn't show up; someone would have called, and if he didn't answer the phone someone would have come by. Maybe the show people had still been there when they came. The word would have spread through school that he was still alive.

He tried to imagine LaVon and Kippie and Pope hearing that Mr. Machine, Mr. Bug, Mr. Carpenter was still alive. They'd be afraid, of course. Maybe defiant. Maybe they had even confessed. No, not that. LaVon would keep them quiet. Try to think of a way out. Maybe even plan an escape, though finding a place to go that wasn't under Utah authority would be a problem.

What am I doing? Trying to plan how my enemies can escape retribution? I should call the marshals again, tell them what happened. If someone hasn't called them already.

His wheelchair waited by his bed. The show people had shined it up for him, got rid of all that muck. Even straightened the computer mounts and tied it on, jury-rigged it but it would do. Would the motor run, after being under water? He saw that they had even changed batteries and had the old one set aside. They were good people. Not at all what the stories said about show gypsies. Though there was no natural law that people who help cripples can't also seduce all the young girls in the village.

His arms hurt and his left arm was weak and trembly, but he managed to get into the chair. The pain brought back yesterday. I'm alive today, and yet today doesn't feel any different from last week, when I was also alive. Being on the brink of death wasn't enough; the only transformation is to die.

He ate lunch because it was nearly noon. Eldon Finch came by to see him, along with the sheriff. "I'm the new bishop," said Eldon.

"Didn't waste any time," said Carpenter.

"I gotta tell you, Brother Carpenter, things are in a tizzy today. Yesterday, too, of course, what with avenging angels dropping out of the sky and taking away people we all trusted. There's some says you shouldn't've told, and some says you did right, and some ain't sayin nothin cause they're afraid somethin'll get told on them. Ugly times, ugly times, when folks steal from their neighbors."

Sheriff Budd finally spoke up. "Almost as ugly as tryin to drownd em."

The bishop nodded. "Course you know the reason we come, Sheriff Budd and me, we come to find out who done it."

"Done what?"

"Plunked you down that wash? You aren't gonna tell me you drove that little wheelie chair of yours out there past the fringe. What, was you speedin so fast you lost control and spun out? Give me peace of heart, Brother Carpenter, give me trust." The bishop and the sheriff both laughed at that. Quite a joke.

Now's the time, thought Carpenter. Name the names. The motive will be clear, justice will be done. They put you through the worst hell of your life, they made you cry out for help, they taught you the taste of death. Now even things up.

But he didn't key their names into the computer. He thought of Kippie's mother crying at the door. When the crying stopped, there'd be years ahead. They were a long way from proving out their land. Kippie was through with school, he'd never go on, never get out. The adult burden was on those boys now, years too young. Should their families suffer even more, with another generation gone to prison? Carpenter had nothing to gain, and many who were guiltless stood to lose too much.

"Brother Carpenter," said Sheriff Budd. "Who was it?"

He keyed in his answer. "I didn't get a look at them."

"Their voices, didn't you know them?"

"No."

The bishop looked steadily at him. "They tried to kill you, Brother Carpenter. That's no joke. You like to died, if those show people hadn't happened by. And I have my own ideas who it was, seein who had reason to hate you unto death yesterday."

"As you said, a lot of people think an outsider like me should have kept his nose out of Reefrock's business."

The bishop frowned at him. "You scared they'll try again?"

"No."

"Nothin I can do," said the sheriff. "I think you're a damn fool, Brother Carpenter, but nothin I can do if you don't even care."

"Thanks for coming by."

He didn't go to church Sunday. But on Monday he went to school, same time as usual. And there were LaVon and Kippie and Pope, right in their places. But not the same as usual. The wisecracks were over. When he called on them, they answered if they could and didn't if they couldn't. When he looked at them, they looked away.

He didn't know if it was shame or fear that he might someday tell; he didn't care. The mark was on them. They would marry someday, go out into even newer lands just behind the ever-advancing fringe, have babies, work until their bodies were exhausted, and then drop into a grave. But they'd remember that one day they left a cripple to die. He had no idea what it would mean to them, but they would remember.

Within a few weeks, LaVon and Kippie were out of school; with their fathers gone, there was too much fieldwork and school was a luxury their families couldn't afford for them. Pope had an older brother still at home, so he stayed out the year.

One time Pope almost talked to him. It was a windy day that spattered sand against the classroom window, and the storm coming out of the south looked to be a nasty one. When class was over, most of the kids ducked their heads and rushed outside, hurrying to get home before the downpour began. A few stayed, though, to talk with Carpenter about this and that. When the last one left, Carpenter saw that Pope was still there. His pencil was hovering over a piece of paper. He looked up at Carpenter, then set the pencil down, picked up his books, started for the door. He paused for a moment with his hand on the doorknob. Carpenter waited for him to speak. But the boy only opened the door and went on out.

Carpenter rolled over to the door and watched him as he walked away. The wind caught at his jacket. Like a kite, thought Carpenter, it's lifting him along.

But it wasn't true. The boy didn't rise and fly. And now Carpenter saw the wind like a current down the village street, sweeping Pope away. All the bodies in the world, caught in that same current, that same wind, blown down the same rivers, the same streets, and finally coming to rest on some snag, through some door, in some grave, God knows where or why.

Special thanks to Tor for giving permission for IGMS to reprint The Folk of the Fringe which is still in print.

on the art and business of science fiction writing.

Over five hours of insight and advice.

Recorded live at Uncle Orson's Writing Class in Greensboro, NC.

Available exclusively at OSCStorycraft.com

We hope you will enjoy the wonderful writers and artists who contributed to IGMS during its 14-year run.