Peter Wiggin was supposed to spend the day at the Greensboro Public Library, working on a term paper, but he had lost interest in the project. It was two days before Christmas, a holiday that always depressed him.

Last year he tried to get off the Christmas juggernaut. "Don't get me any gifts," he had said to his parents. "Put the money into mutual funds and give it to me when I graduate."

"Christmas drives the American economy," Father said. "We have to do our part."

"It's not up to you what other people do and don't give you," said Mother. "Invest your own money and don't give us gifts."

"Like that's possible," said Peter.

"We don't like your gifts anyway," said Valentine, "so you might as well."

This stung Peter. "There's nothing wrong with my gifts! You sound like I give you used Band-aids or something."

"Your gifts always look like you bought the cheapest things on sale and then decided after you got them home who you'd give them to."

Which exactly nailed the process Peter went through. "Gee, Valentine," said Peter. "And everyone calls you the nice one."

"Can't you two ever stop bickering?" said Mother wistfully.

"Peace on Earth, good will toward brats," said Peter.

That was last year. He gave them the gifts he'd already bought, and he didn't notice anybody turning them down.

But he also took Mother's advice. During the past year, Peter's investments -- anonymous investments, of course, since he was still underage -- had done very well, and in November he sold off enough shares to pay for some nice gifts for the family. Nobody was going to say there was anything wrong with this year's crop. Though he couldn't spend too much, or Dad would start to get way too curious about where Peter's money was coming from.

Since Peter was not really working on his paper, he happened to notice when one of the girls from school sat down at a different table and spread out her books. Since they had the same high school class, she was no doubt working on the same assignment -- a paper on something about Rome, as if the subject hadn't already been done to death by real scholars over the centuries. What were high school students going to add to the sum of human knowledge about the old empire? Peter couldn't think of a single topic that didn't bore him.

But maybe she had something interesting. What was her name? Mirabella, that was it -- Italian for "Look! Pretty!" The name fit well enough, but Mirabella, being sensible, had opted for the nickname Bell.

Peter got up, walked over, and sat down across the table from her. "What's your topic?" he asked.

She looked at him with an odd expression, but he was used to that. Being younger than the other students meant permanent pariah status. At school, he ate alone; but he preferred it that way. None of the other kids interested him. She didn't interest him. But right now talking to somebody seemed better than staring off into space trying to think of a topic.

Eventually she decided to talk to him. "I like Cicero," she said. "But in a weird way I also like Cato. 'Carthage must be destroyed!'"

Peter nodded and smiled. "Both proof that neither cleverness nor grim determination are enough to make a great statesman."

"Yeah, well, they're famous Romans, which means they're dead but at least something is written about them, and I can write a paper with three sources and be done with it."

He suppressed a sigh. Here he was worried about finding a topic that hadn't already been written about, and all she cared about was getting her three sources. But he didn't show his scorn. He remembered what Valentine always said about him -- how he wasn't a nice person. He could be nice.

"Would you like some help?" he asked.

She sat up straight. "You are really a piece of work," she said.

"Excuse me?"

"What is there about me that suggests I need your help?" she said. "I'm still laying out my books to take notes. How could I possibly be doing anything wrong yet?"

Peter was stunned by her response. "I just offered. It didn't imply anything."

"Oh, wait," she said. "I get it. This was a come-on. Haven't you noticed that you're, like, twelve? Try again when you reach puberty."

So much for trying to be nice. He wasn't twelve, he was fourteen, so even though he was younger than the other seniors, he was still the right age for high school. And puberty was well under way. He shaved every day and it wasn't just wishful thinking. But what was the point of explaining anything? He tried to be nice to somebody and look what happened. Valentine was full of crap. They were all full of crap. Being nice just got you dumped on.

"Merry Christmas," Peter said.

"Yeah, whatever," said Bell.

Peter walked away from Bell's table. He knew now that he wasn't going to write the paper, not today. Though he had a vague idea of writing about Hannibal, a great general who was never able to win his war even though he won every battle, and finally his own people betrayed him.

I'm one up on Hannibal. Nobody ever gave me an army, and people already betray me all the time instead of waiting till I've actually done anything important.

I'll never do anything important. That was decided when I was still a toddler and they requisitioned Val and Ender to try to do a better job of it.

He left the library and got on his bike. His Christmas shopping was done. It's not as if he had any friends to call up and hang out with. There was nothing to do in the miserable town of Greensboro where his parents had forced him to live. In a real city there were fast tubes to take you anywhere. Here, it was the bus or the bike, and neither one took you anywhere interesting because there was nothing here but the same stores as the rest of America, plus trees.

He parked his bike in the garage, next to Mom's -- Val and Dad were both out, apparently, since their bikes were gone -- and went into the house. He was still in a foul temper from his confrontation with Bell, but he was determined to be nice and not pick a fight with anybody.

He came into the living room to find Mother crying over -- of all things -- a Christmas stocking.

He tried joking. "Don't worry, Mother," he said. "You've been good. It won't be coal this year."

She gave him a thin little courtesy laugh and quickly stuffed the stocking back into the box it was stored in. Only then did he realize whose it was.

"Mom," he said. He couldn't help the tone of frustration and reproof in his voice. It's not like Ender was dead. He was just in Battle School.

Mom got up from the chair where she was sitting and headed for the kitchen.

"Mom, he's fine."

She turned to him, gazed at him steadily with eyes like fire, though her voice was mild. "Oh -- you've had a letter from him? A phone call? A secret report from the school administrators that they didn't provide to Ender's parents?"

"No," said Peter, still unable to keep the impatience from his voice.

Mother smiled acidly. "Then you don't know what you're talking about, do you?"

Peter resented the contempt in her tone. He hadn't done anything and she was snapping at him just like Bell had. Well, he could say what was on his mind, too. "Stroking his stocking and crying over it, that's supposed to make anything better?"

"You really are a piece of work, Peter," she said, pushing past him.

The same thing Bell had said. What did that even mean? "A piece of work?" Why was it a bad thing? Idiomatic expressions used by idiots.

He followed her into the kitchen. "I bet they hang up stockings for them up in Battle School and fill them with little toy spaceships that make cool shooting noises."

"I'm sure the Muslim and Hindu students will appreciate getting Christmas stockings," said Mother.

"Whatever they do for Christmas, Mother, Ender isn't going to be missing us."

"Just because you wouldn't miss us doesn't mean he doesn't."

He rolled his eyes. "Of course I'd miss you."

Mother said nothing.

"I'm a perfectly normal kid. So's Ender. He'll be busy. He's getting along fine. He's adapting. People adapt. To anything."

She turned slowly, reached across and touched his chest, then hooked a finger through the neckline of his shirt and drew him close. "You never adapt," she whispered, "to losing a child."

"It's not like he's dead," said Peter.

"It's exactly like he's dead," said Mother. "I will never again see the boy who left here. I'll never see him at age seven or nine or eleven. I'll have no memories of him at those ages, only what I can imagine. That's what the parents of dead children have. So until you actually know what you're talking about, Peter, why don't you put a lid on your advice to grieving mothers?"

"Merry Christmas to you too," said Peter. He left the room.

His own bedroom, when he entered it, felt strange to him. Alien. Bare. There was nothing there that expressed a personality. That had been a conscious decision on his part -- anything individual that he put on display would give Valentine an advantage in their endless dueling. But at this moment, with Mother's accusation of his inhumanity still ringing in his ears, his bedroom looked so sterile that he hated the person who would choose to live in it.

Why do I even try to adapt to this world? I'm never going to fit in, not with my family, not at school. And when I graduate and get my college degrees -- from a university where I won't fit in -- who will hire me? Who will supervise me? That's a laugh. I'm not of the same species, and they know it. Like an immune system, they sense my presence and seek to reject me. The human race is allergic to me. I give humanity a rash. Wherever I go, people scratch at me.

He wandered back into the living room. Mother wasn't there -- still in the kitchen, probably. He reached into the box of Christmas stockings and pulled out the whole stack.

Mother had cross-stitched their names and an iconic picture on each stocking. How domestic of her. His own stocking had a spaceship. Ender's stocking had a steam locomotive. How ironic. Ender was the one in space, the little twit, while Peter was stuck on land with the locomotives.

Stuck riding between rails, to destinations someone else had already chosen. While Ender had an infinitely variable future. It was as if Ender had crushed Peter under his shoe.

Peter thrust his hand down into Ender's stocking and started making it talk like a hand puppet. "I'm Mommy's bestest boy and I've been very very good."

There was something in the toe of the stocking. Peter reached deeper into the sock, found it, and pulled it out. It was just a five-dollar piece -- a nickel, as people had taken to calling them, though it was supposedly a hundred times the value of that ancient coin.

"So you've taken to stealing things out of other people's stockings?" said Mother from the doorway.

Peter felt as embarrassed as if he had been caught in an actual crime. "The toe was heavy," he said. "I was seeing what it was."

"It wasn't yours, whatever it was," said Mother cheerily.

"I wasn't going to keep it," said Peter. Though of course he would have done exactly that, on the assumption that it had been forgotten and would never be missed.

But that was the stocking she had been holding and weeping over. She knew perfectly well the nickel was there.

"You still put stuff in his stocking every year," he said, incredulous.

"Santa fills the stockings," said Mother. "It has nothing to do with me."

What was scary was that there was no irony in her voice. For all he knew, she believed it. Peter shook his head. "Oh, Mother."

"It has nothing to do with you," said Mother. "Mind your business."

"This is morbid," said Peter. "Grieving for your hero-boy as if he were dead. He's fine. He's not going to die, he's in the most sterile, oversupervised school in the universe, and after he wins the war he's going to come home amid cheers and confetti and give you a big hug."

"Put back the five dollars," said Mother.

"I will."

"While I'm watching."

Unbelievable. "Don't you trust me, Mother?" asked Peter. He spoke in a sarcastically aggrieved voice, to hide the fact that he really was hurt.

"Not where Ender is concerned," said Mother. "Or me, for that matter. The coin is Ender's. It shouldn't have anybody's fingerprints on it but his."

"And Santa's," said Peter.

"And Santa's."

He dropped the coin down into the sock.

"Now put it away."

"You realize you're making it more and more tempting to set this thing on fire," said Peter.

"And you wonder why I don't trust you."

"And you wonder why I'm hostile and untrustworthy."

"Doesn't it make you just the tiniest bit uncomfortable that I have to wait until I'm sure you're not going to be home before I can allow myself to miss my little boy?"

"You can do what you want, Mother, whenever you want. You're an adult. Adults have all the money and all the freedom."

"You really are the stupidest smart kid in the world," said Mother.

"Again, just for reference, please take note of all the reasons I have to feel loved and respected in my own family."

"I meant that in the nicest, most affectionate way."

"I'm sure you did, Mommy," said Peter. He put the stocking into the box.

Mother came over as he was starting to rise out of the chair. She pushed him back down, then reached into the box and took out Ender's stocking. She reached inside.

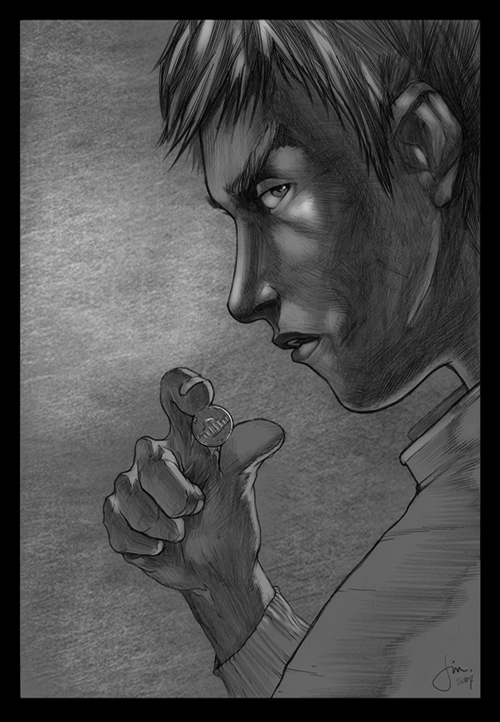

Peter took the coin out of his shirt pocket and handed it to her. "Worth a shot, don't you think?" He had long since learned the skill of palming coins, but of course Mother knew that, and even though she probably hadn't caught the movement, she knew it was something he was capable of.

"You're still so envious of your younger brother that you have to covet everything that's his?"

"It's a nickel," said Peter, "and he isn't going to spend it. I was going to invest it and let it earn him some interest before he gets home in, oh, another six or eight years or whatever."

Mother bent over and kissed his forehead. "Heaven knows why I still love you." Then she dropped the coin into the stocking, put the stocking into the box, reached out and slapped Peter's hand, and then took the box out of the room.

The back of Peter's hand stung from the slap, but it was where her lips had touched his brow that his skin tingled the most.

Peter took the tube to school. All the buildings were locked, of course, because of the holidays, but he walked between buildings, looking into windows at the desks lined up in rows.

The desks were all so well-behaved. They stayed in place, made no noise, remained alert at all times. No wonder the teachers all seemed to be talking to the desks -- the desks were the only things acting properly.

The students, on the other hand, were unruly, unpredictable. They absorbed only what interested them enough to imprint in memory. Some of them actually cared about what the teachers thought of them, and learned in order to please the authority figures. Some of them did not care and learned only what was repeated often enough to penetrate their memories without any effort at comprehension.

But what about Peter? He should have been the ideal student. He came in knowing more than any of the other students, even in this school for gifted children. He always grasped everything immediately. He wanted to follow up, to penetrate, to learn more. He raised his hand. And the teachers' eyes did this little flickering thing, and their pulse quickened, they breathed more rapidly, and they looked for anyone else to speak to, anything else to talk about, just so they didn't have to deal with Peter Wiggin.

They were afraid.

Of what? They had all the power.

Or did they? His questions were sincere, but they also were dangerous -- he was asking the teacher to go behind the curriculum, to look at the roots of things. And that's not what they were trained to do. Most of them had never even thought about the issues that Peter raised.

But so what? Why couldn't they look at the question and realize that it was interesting? Why couldn't they leap into it the way Peter wanted to and explore it and speculate and try out new ideas? Or challenge the old ones?

Instead they usually resorted to, "That will come later, Peter," or "We have to cover a certain amount of material today, Peter, and digressions don't help." Never even an attempt to answer.

They were so afraid of appearing ignorant or stupid in front of the rest of the class that they hid behind their authority and silenced him. The kids who were openly hostile they could deal with, tease, develop a relationship. But Peter Wiggin -- he had to be locked into an isolation cell in the midst of the classroom, kept from discussion, treated as if he didn't exist. If he were mentally retarded, asking questions like, "Where can I buy gum?" or "What do you call the color of your shirt?" they could not treat him with more contempt.

The result was that Peter did not speak in class any more than he could help -- which just about killed him, since so much of what they taught was shallow or insufficient or mechanical or flat wrong. The other kids weren't geniuses but they were bright, they could have learned at a much deeper level and it might even have woken some of them up. But the teachers were talking to the desks, and to the kids who acted like desks.

Peter's petty vengeance was never to fulfil any of their assignments as given. Whatever they assigned, he would look at it and find a perverse way to do something much deeper and more interesting. Then he would turn it in on the date the original assignment was due. Like writing about Hannibal when they assigned a paper on Rome. You want Rome? I'll give you Carthage.

When he started doing this, some of the teachers gave him Fs. "Fulfil the assignment," they wrote. Peter didn't mind. An F from an idiot who valued obedience over achievement was like a gold star. As the Fs piled up during the first quarter, he sent his papers to various journals -- anonymously, of course, so that his age and lack of credentials were not so obvious -- and while the peer-reviewed journals were out of the question, there were several peripheral journals that posted his F papers in order to spark discussion among the adult scientists and historians and critics. On the nets he was taken seriously.

At the end of that first quarter of open rebellion, his parents were called in to consult about his failing grades. Even on the final exams for the quarter he had answered, not the questions they asked, but the questions he thought they should have asked. So his grades in these classes were perfect Fs.

His answer was to bring his laptop to the conference and sign on to the net. Then he showed his parents, the principal, and the teachers each of the places online where his papers had been published and adults were discussing them -- often with excitement, using them as springboards for long and sometimes heated discussion.

"Are you saying that you plagiarized these from the net?" asked one of the teachers.

Father turned to her and did not attempt to hide his scorn. "He's showing you that after you failed his paper, he got it published on a professional forum."

The teacher stiffened. "The goal of the class is to cover the material assigned and fulfil the assignments given."

"Well," said Father, "that's the wrong paradigm. The goal is supposed to be guiding the students to complete understanding of the material. What I'd like to know is how you imagine Peter could write something like this without a complete understanding of the material you're teaching?"

After much hemming and hawing, it finally came down to this. The teachers said, though not in so many words, that they didn't have time to read Peter's papers. They were simply too demanding. They only had time to evaluate student work that was attempting to fulfil the assignment. Just because Peter's writings demonstrated that he had a complete grasp of the material did not make it any less time-consuming for them to read and evaluate.

Father stood up then and said, "Then I suggest you give Peter the A he obviously deserves, and save his papers to read over the summer. Consider it your inservice professional training. But don't treat a student like Peter as if he were failing, when the failure is obviously elsewhere." With that, Father simply walked out of the conference. And from then on, Peter got automatic As on everything he wrote. As far as he knew, no one read his papers now.

The teachers hated him.

And so did the other students. He was treated as if he didn't exist. Completely ignored. Even by the girls. And if he had any doubts about it, Bell had made it clear that their ignoring him was not because they didn't notice him. It was active ostracism. They hated him before he opened his mouth.

And that made no evolutionary sense, as far as Peter could tell. He and these girls were at the age when hormones were guiding most of their waking thoughts. These girls should be looking for males with the markers of power and achievement. Future providers and protectors. Peter was younger than most, and smaller, but he was clearly the most intelligent boy they knew, destined for greatness, and yet they shunned him and looked for boys with good looks and cool clothes and more than a hint of violence about them.

They're chimps, searching for the alpha male. In a civilized society, I'm the most alpha male they can possibly find -- but no, they aren't looking for human alphas, marked by intellect, creativity, boldness. They're looking for chimp markers: physical strength, aggression, violence. Which male will prevail in physical combat? I want his sperm!

Chimpettes.

Peter looked at his reflection in the glass of the classroom window. He was actually rather tall -- for his age. He had no excess body fat, and he was reasonably good in Phys. Ed. He could run, he could hit a ball with a stick, he could kick a goal. He wasn't the best but he was definitely an asset to teams and held his own in one-on-one games. Other guys at his level were taken seriously by girls. Why did his intellect banish him from alpha status?

Deep down in their chimp minds, the girls must be unconsciously terrified that any children I sired would have huge brains and therefore would be painful to deliver through their skinny little pelvises.

Or maybe it was something else. Maybe it was the anger in his eyes, which he could see even in the poor reflection in the glass.

Except ... wasn't anger a sign of aggression? Chimp-girls like these should be drawn to his aggression. And yet they were repelled. Everyone was repelled.

Even his family hated him. Father could come and stand up for him, treating his teachers and principal with the scorn that they deserved -- but it didn't mean Father liked Peter. At home, Father never sought conversation with him.When Peter came to him, Father would converse with him, and at a very high level, with real respect. Yet Peter always had to initiate it. Father never looked for a chance to be with him.

And Mother -- well, she talked to Peter all the time, but even when she said she loved him, it was always in some ass-backward way that was as much of an insult as a protestation of love. It was always about how she loved him despite his complete unloveability.

It had always been that way, he could see that now, even when he was little. But not until Ender came along was it clear to Peter how he was despised. Only when he could see how his parents and Valentine doted on Ender did he realize what was so painfully missing from his own life. That's what love for a boychild looks like, and I would never have known about it if I hadn't seen the way they treat Ender.

He studied his reflection in one of the windows of the school. What was it that made people detest him?

Somebody like me should be admired, Peter thought fiercely. I should be looked up to. I should be surrounded by people who want to hear what I'm saying, to know what I'm thinking, to provide me with whatever I want, to have my friendship.

That's the research paper I should be writing. Speculations on the self-defeating rejection of the superior offspring among primates.

Why are they afraid of me?

Why aren't they more afraid?

Peter stood at the edge of the school property and realized, for the second time that day, that there was nowhere he could go, nothing he could do. He would go home because there was no other indoor space where he actually had a right to eat or sleep. As a minor, he could not go anywhere interesting.

So, again, he went home, walking this time in the darkening evening, looking at the Christmas lights come on along the residential streets. Ho ho ho. Aren't we bright and jolly.

Valentine walked into his room -- without knocking, of course -- and saw him lying on his bed, watching a vid on the far wall.

"Baboons," she said. "Studying up to join a troop?"

"Trying to identify the genetic source of your best features," said Peter. "When exactly is it that your butt turns red?"

"Don't you hear yourself? How sick you sound?"

Finally Peter turned to look at her. "You chose to come in and start insulting me. How does that make me the sick one?"

She just shook her head. "Golly, Peter. You really have the Christmas spirit, don't you? Somehow you've got it in your head that you're Tiny Tim. Life's just treatin' you so bad."

"'Home is where, when you have to go there, they treat you like shit.'"

"From Dickens to a coprophiliac version of Frost. Peter, have you actually noticed that nobody likes you? Is that what this is about? Because if it is, let me tell you a secret. When you spend your life being cruel to everyone around you, it doesn't build up this vast reservoir of love just waiting to be released when you need some."

This was so outrageous Peter could hardly believe it. "I've never been cruel to anybody."

"Are you insane?" asked Valentine. Then she laughed. "I know, the lunatic is the last to know. But seriously, Peter, don't you get it? Mom and Dad think that the only reason Ender said yes to Battle School and left us when he didn't have to is because he was scared of you."

"Why would he be scared of me?" asked Peter. And then of course he remembered that the very day Ender left, he had threatened to kill him. "I was joking."

"Oh, really? You said that you would pretend that it was a joke, but then one day, when nobody was expecting anything, when we'd forgotten all about it, there'd be a accident."

"I thought Ender was supposed to be so smart -- he knew I didn't mean it."

"I'm smart too, Peter, and I know you did mean it."

"Did not." He said it in a completely bored tone, so she'd know he didn't actually care what she believed.

"At the time you did. Maybe at this moment you don't. But if Ender were still here, then he'd annoy you again -- by being better than you, no doubt, that always seemed to be the trigger -- and then you'd mean it again."

"At no point in his life has it bothered me that Ender was better than me, mostly because at no point in his life has he ever been better than me."

"A statement you can make without refutation only because Ender is gone so there's no way to bring up the obvious evidence."

"What pisses me off about Ender," said Peter, "is the way everybody loves him no matter what he does. I'm surprised Mom and Dad didn't save his used diapers in a shrine in the back yard."

"Did you know? I used to love you," said Valentine.

The words stung more than Peter would have imagined. "I'm glad you got over it."

"Yeah," she said. "You managed to make me so ashamed of it I tried to pretend it was never true. But it was. I worshiped the very ground you knocked me down on."

"And then what happened?"

"Ender was born," said Valentine. "To show me what a brother was, so I finally realized you weren't one."

"It's a genetic thing," said Peter. "Once a brother, always a brother."

"You can't be a brother," said Valentine, "when you live in a universe where only you exist. You're a narcissist, Peter. The navel of the universe, and you spend your life contemplating yourself."

"And yet you still came into my room."

"Because Mom was crying in the living room," said Valentine. "I just wanted to know what you did."

"She was crying before I ever talked to her. About baby Ender's widdo bitty stocking."

"Ah, yes. I bet you were really warm and sympathetic."

"No," said Peter. "I was cruel."

When he said it, he realized that it was true.

But Mother had been cruel to him, too. The very act of worshiping Ender's damn Christmas stocking was cruel.

"Get out of my room," Peter said to her. "And close the door behind you."

She looked at him, made as if to say something, then thought better of it, apparently, because she only turned around and left.

She even closed the door. Gently. No wonder everyone thought she was so nice.

Back when Peter was five, he had read in one of Dad's science websites how the human shoulder clearly evolved from the brachiating arm of the other primates to a throwing arm. The first missile weapon, said the article, was the thrown stone, which could kill a small animal at fifty feet.

Peter had taken that as a challenge, and even though he was still too young to expect a fifty-foot range, he could at least work on his aim. By the time he was six, practicing almost every day for two years, he could clip a tulip off its stem from twenty feet away. He thought that was about as good as a primate his size could be expected to do.

Then he started working on moving targets. Squirrels were pretty easy to hit, though at his age at the time he didn't throw with much force and they only got annoyed and scampered away. Lizards were a lot harder, because they tended to dodge the moment his arm started swinging -- but when he hit them, he knocked them right out.

For a while he saved all the lizard bodies but then Mom found them and threw them out, along with a lecture about how human beings were supposed to be stewards of the Earth, and animals were only to be killed for need. In vain did he explain that if he ever needed to kill an animal, it might be better if he had practiced a little first.

So he no longer kept his trophies. And after a while it was just too easy to keep doing it every day. Still, he knew a useful skill when he acquired it, and so over the years he had practiced every week or so. By the time he was ten, he could knock down squirrels every time -- and now from fifty feet away, just as that old article had promised. He had a good arm.

His practice never seemed to help him with softball or baseball, though. The balls were too big and soft. He could have pitched a stone into the strike zone every time, but it didn't come up very much in games. He wasn't allowed to aim for a real target, like the head.

It was stones with a nice heft that did the job right. He could throw them faster, get more spin on them, control the arc perfectly, and hit squirrels on the head, not just knocking them down, but knocking them out. Then it was a simple matter to pick them up by the head, give a nice snap with that good throwing arm, and break the neck. Completely painless to the unconscious squirrel.

At age ten, Peter took a lot of satisfaction from knowing that if civilization ever broke down and he had to live on what he could kill, he wouldn't go hungry. Not that he expected the breakdown of civilization. It was just good to know that he had learned how to use his arm for what it had evolved to do.

But he did something else, too. Just a few times, when he had an unconscious squirrel in his hands, he didn't snap the neck. Instead, taking his dissecting kit from school -- he was in eighth grade, and they cut up lots of things and took the kits home, so clearly they expected him to find interesting subjects for private study -- he staked out the squirrel and flayed it alive.

Twice he did it and the squirrel never recovered consciousness. He peeled the skin back, then sectioned and lifted off the anterior rib cage, without piercing any of the organs underneath. He really had a deft hand.

I could be a surgeon, he thought, if I didn't know it was a waste of time for me to do a job that only affects one person at a time.

He left the squirrels staked out for Valentine to find.

The third time, though, the squirrel had woken up during the flaying. He had not imagined that a squirrel could make a sound like that.

He tried to continue with the operation, but he couldn't concentrate and his hand trembled. Or maybe it was deliberate. Unconsciously deliberate? Was that possible? But the scalpel nicked the heart and the squirrel bled out in moments.

That one he didn't leave spread-eagled for the insects. He dug with his hands in the red clay that passed for soil and buried the squirrel.

He remembered the place in the woods behind the house, and went there now, though it was nearly dark. He didn't know what he expected to see. There was nothing. Just leaf-covered soil. He scraped away the leaves with his shoes and exposed the soil be there wasn't even a mound anymore. Nothing to suggest that the squirrel had ever been buried there.

What was I thinking? Peter asked himself. The first two squirrels should have stopped me. Why was I going on with it? I had learned anything I was going to learn from the first one. It wasn't science, it wasn't curiosity. I was starting to like it. To like knowing that they were alive while I did it to them.

Is that what all these people see in me? The person who could vivisect a living creature?

Why can't they see the person who couldn't stand to hear a squirrel scream? The person who buried the body instead of displaying it?

No, Peter told himself. That's backward. They see the person who would leave those vivisected corpses to be discovered. Just because one time I chose not to do it doesn't change what I am.

When I sat across from Bell today in the library, thought Peter, I offered to help her. I was being nice.

But it was an act. I was pretending to be nice. She saw through me. She knew what I really was. A predator.

Peter leaned against a tree. Felt the bark pressing against his back through the shirt.

They are right about me. They should hate me and fear me. They should reject me and exclude me. I don't belong among humans.

He slid very slowly down the trunk. The bark grabbed at his shirt and pulled it up as he slid down, and the bare skin of his back scraped against the tree and it hurt and he kept doing it because he wanted to hurt. He deserved to hurt.

I didn't want to hurt anybody, he told himself. As soon as I realized how much pain the squirrel felt, I stopped. And I never did it again. Whatever I am, that's not who I want to be. That must count for something.

What was I doing, if I didn't enjoy causing pain? Was it all just so I could show Valentine? Scare her? Sicken her?

It wasn't about Valentine. That had been an afterthought. No, it was something I wanted to do with the squirrel. To the squirrel. Get from the squirrel.

He had read a lot of psychology, more for the amusement value than anything else. Once you stepped outside the area of drug therapy for defective brains, psychology seemed indistinguishable from religion to him, and he had no use for either.

But now he tried to imagine: What would a talk therapist say about why I took the skin off living squirrels and opened their thoraces so I could see their beating hearts?

Symbolic: Because I had no heart, I needed to see one. No, because I was unloved I doubted that people had hearts and ...

That was too silly even for this game.

It wasn't about the beating heart. It was about taking control of it. That's what a good therapist would say. I was seeking control because I feel powerless.

And sitting there on the ground, his back stinging from having scraped against bark, he knew he was on to something. It was about power. It was always about power.

It's not that they loved Ender, it's that their love gave him so much power over them. He was oblivious to it. He couldn't see how they shaped their lives around him, always oriented to him -- and away from me. I didn't want their love, I wanted the power that Ender had, the ability to shape things the way he wanted them. I could never do it. I could never get a soul to act the way I wanted.

He found himself getting so excited he wanted to cavort like a madman. Instead he stayed on the leafy forest floor and traced designs with his finger on the bare ground of the squirrel's grave. A circle -- himself -- all by himself. No connections. Power comes from getting other people to do things your way. Power comes from obedience.

And how do you get obedience? Peter had always tried to get it by pushing, by demanding, by grabbing. He had let his hunger for power show.

And it's not as if that couldn't work. There had been plenty of coercive dictators in the history of the world. They got their way by creating fear in the hearts of others. They were willing to kill anyone that got in their way. And so the others complied. Did what they were told.

But nothing those men created outlasted them. As soon as they died or fell from power, or their dynasty ended, their statues and pictures were torn down or flung onto the fire.

It was the ones who were loved who were the most successful. Hitler terrorized people, yes, but there was more to him than that. He was also worshiped -- not by everybody, but by many. How did he do that? Those eyes, always so sad, looking like he was on the verge of weeping. Or was it the sternness of his face? Was he a father figure, the judge, and they looked to him for approval and he gave it to them: You are the great ones, you Germans, you deserve better, I judge you and find you worthy!

But Hitler's empire didn't last, either. It was too destructive, what he did with his power. He tore things down, he built nothing.

Augustus, thought Peter. He's the one. Started out as the frail, conniving, brilliant, ambitious, and very young Octavian. Caesar's heir -- even if he had to destroy Caesar's friends to climb into the martyred hero's chair. Octavian was careful that he cast himself, not as a brutally ambitious warrior, but as the man who would end wars and save the Roman world. He allowed them to call him by the old-fashioned honorific "Augustus," but he preferred the title "first citizen." Princeps. Prince.

It didn't matter what they called him. Whatever word they used would come to mean what they knew he was: the rightful ruler.

It was possible for most Romans to believe that the Republic still existed, while Augustus was alive. He understood how civilization worked. He tried to imbue Roman society with the stern virtues that had created their greatness in the first place.

He gave them peace. And it lasted.

But how did he do it? When the war began he was nothing. Nobody tagged him as a great general -- and he wasn't one, not really. His power came from convincing people that he truly had their best interests at heart -- that all he cared about was restoring Rome to peace and prosperity.

That's what I haven't been able to do, thought Peter. I haven't been able to convince a living soul that I care about anybody but me. That there's any ideal that I would sacrifice to serve. Octavian became Augustus because he convinced people that his ambition was never for himself.

And then, when he got power, he continued to act out that script. He really did use his power for the general good of the empire. Not perfectly, certainly -- I could do better than he did -- but in the main he succeeded. Things were better for almost everyone because of his victory, and he governed well.

I cannot get power and control with my stone and my scalpel. No matter what I did to the squirrels, they ended up dead, and from that moment on I had no power over them.

Power flows to the one who convinces everyone that by obeying him, their own lives will be better.

And in that moment he set aside the religion of talk therapy and took on the religion of his parents. "Whoever would be greatest among you, let him be the servant of all." This was not niceness, what Jesus was saying. It was almost Machiavellian in its forthright deviousness. If you want to be the greatest, to have real power, then you must convince everyone that you serve them. And here's the clincher: For it to last, you really have to do it. So even if you're pretending to care about people, you can never stop pretending, and you have to deliver on the promise. So, in the end, you really are the "servant of all."

I finally get it, Jesus, said Peter silently. What you said to that other Peter, Simon Peter: If you love me, feed my sheep. If you want my power, then convince the sheep that you care about them more than you care about yourself.

But I don't care about them.

But if I act as if I care, and devote my whole life to doing what really will make them happy and give them peace and prosperity, then what does it matter that my deepest motive was to make myself master of the world? If the world I rule is happier and better off because I rule it, and my hand sits lightly on the reins of power and few directly feel the tug of my power, then I can build something that will outlast me.

He had the perfect people to practice on.

The next day, the last day before Christmas, he redid all his Christmas gifts.

So on Christmas morning, while he still gave Father and Mother and Valentine the gifts he had bought for them, he accompanied them with something else.

He wrote them each a letter. To Father, he wrote of how much it meant to him that he had stood by Peter when the teachers were failing him in school. "I thought I was alone," he said, "but then you stood with me. That was worth more than any grade. You could have rebuked me and forced me to comply with them; instead you gave my work respect and stood beside me against the world. That's the man I want to become: That's the man you are."

Father's eyes got all teary when he read it. He refused to read the letter aloud or show it to anyone else. "It's between Peter and me," he said gruffly.

To Valentine, Peter wrote about how well she had cared for Ender. How she had protected him. "It made me angry at the time, because I was so childish I thought that you had chosen sides in a war, and I was the one you rejected. But I see now that I was completely wrong. Instead, you stood for peace and against war; all I had to do was stop fighting for your love, and I would have had it. It was the fighting that built the wall between us. I should have seen that the love was in your nature. It was who you are, and if I had only let you, the same kindness you showed Ender could have been mine."

She looked up from the letter with suspicious eyes. But of course he couldn't win her over with a single letter. She had seen most of his lies; he had told her the truth behind too many of them for her to take anything he said or wrote at face value. It would take time, with Valentine. But at least she didn't jeer at the letter. That was a step.

To Mother, Peter wrote nothing. He had made a collage of pictures of Ender from the computer archive, and framed the resulting art with a single nickel in the middle. Not a modern five-dollar piece, but one of the old nickels -- it was the one purchase he had had to make on the day of Christmas Eve, but it wasn't even expensive, the coin dealer had only charged him fifteen bucks for it. The frame was more expensive.

With the framed picture, he had included only the briefest note: A slip of paper on which he had written, "I miss him, too."

Mother wept as she had wept over Ender's stocking. But in the midst of it, she came to Peter and hugged him and he knew that he was on the right track. He could do this thing.

After New Year's, school began again, and Peter made a point of seeking out Bell at lunchtime. She was sitting at her regular table, with her regular friends, and when Peter came up and slid in between two of them and leaned on the table and looked searchingly in Bell's eyes, she was poised to wither him with her scorn.

But he never took his eyes off her face and somehow that silenced her long enough for him to say, "I wanted to thank you, Bell. I understand now how offensive I was, as if I were placing myself above you."

He ignored the other girls saying things like, "Bell's got herself a boyfriend" and "Robbing the cradle, Bell?" He kept his eyes on hers.

"But you were wrong about what I wanted from you," said Peter. "I've seen who you are here at school. The way you're kind to other people, the way you create a haven for the people around you. You know how to be a friend. I wanted to have the gift you give to all of these." He indicated Bell's friends. "I went about it all wrong. I offended you when I never meant to. I just want you to know that what I felt for you was pure respect and admiration. You're a good person, Bell. And even when you were pushing me away, you still taught me some important things. Thank you for that."

Without waiting for the slightest reply, he got up and walked away. Of course, nothing that he said was true. He hadn't noticed much about her except that she was pretty and actually tried to do well in school and if she was an unusually good friend to her friends, Peter would have had no way of knowing it. But he knew that what he said was the kind of thing people liked to think about themselves, and that none of her friends was likely to contradict him. Whether she deserved his admiration or not, she would now believe she had it -- the smartest kid in school admired her! -- and he had done it in a way that showed him to be humble. His guess was that she wouldn't be able to keep her mind off him now, that she would seek him out, that they would become friends, and that through her he would get the chance to play the same game with everyone she knew.

Served her right, the priggish little bitch. Getting her to adore him and serve his interests completely -- that would be the best revenge for the way she scorned him in the library two days before Christmas.

on the art and business of science fiction writing.

Over five hours of insight and advice.

Recorded live at Uncle Orson's Writing Class in Greensboro, NC.

Available exclusively at OSCStorycraft.com

We hope you will enjoy the wonderful writers and artists who contributed to IGMS during its 14-year run.