Han Tzu was the bright and shining hope of his family. He wore a monitor embedded in the back of his skull, near the top of his spine. Once, when he was very little, his father held him between mirrors in the bathroom. He saw that a little red light glowed there. He asked his father why he had a light on him when he had never seen another child with a light.

"Because you're important," said Father. "You will bring our family back to the position that was taken from us many years ago by the Communists."

Tzu was not sure how a little red light on his neck would raise his family up. Nor did he know what a Communist was. But he remembered the words and when he learned to read, he tried to find stories about Communists or about the family Han or about children with little red lights. There were none to be found.

His father played with him several times a day. He grew up with his father's loving hands caressing him, cuffing him playfully; he grew up with his father's smile. His father praised him whenever he learned something; it became Tzu's endeavor every day to learn something so he could tell Father.

"You spell my name Tzu," said Tzu, "even though it's pronounced just like the word 'zi.' T-Z-U is the old way of spelling, called ... 'Wade-Giles.' The new way is 'pinyin.'"

"Very good, my Tzu, my Little Master," said Father.

"There's another way of writing even older than that, where each word has its own letter. It was very hard to learn and even harder to put on computer so the government changed all the books to pinyin."

"You are a brilliant little boy," said Father.

"So now people give their children names spelled the old Wade-Giles way because they don't want to let go of the lost glories of ancient China."

Father stopped smiling. "Who told you that?"

"It was in the book," said Tzu. He was worried that somehow he had disappointed Father.

"Well, it's true. China has lost its glory. But someday it will have that glory back and all the world will see that we are still the Middle Kingdom. And do you know who will bring that glory back to China?"

"Who, Father?"

"My son, my little Master, Han Tzu."

"Where did China's glory go, so I can bring it back?"

"China was the center of the world," said Father. "We invented everything. All the barbarian kingdoms around China stole our ideas and turned them into terrible weapons. We left them in peace, but they would not leave us in peace, so they came and broke the power of the emperors. But still the Chinese resisted. Our glorious ancestor, Yuan Shikai, was the greatest general in the last age of the emperors.

"The emperors were weak, and the revolutionaries were strong. Yuan Shikai could see that weak emperors could not protect China. So he took control of the government. He pretended to agree with the revolutionaries of Sun Yat-sen, but then destroyed them and seized the imperial throne. He started a new dynasty, but then he was poisoned by traitors and died, just as the Japanese invaded.

"The Chinese people were punished for the death of Yuan Shikai. First the Japanese invaded China and many died. Then the Communists took over the government and ruled as evil emperors for a hundred years, growing rich from the slavery of the Chinese people. Oh, how they yearned for the day of Yuan Shikai! Oh how they wished he had not been slain before he could unite China against the barbarians and the oppressors!"

There was a light in Father's eyes that made Tzu a little afraid and yet also very excited. "Why would they poison him if our glorious ancestor was so good for China?" he asked.

"Because they wanted China to fail," said Father. "They wanted China to be weak among the nations. They wanted China to be ruled by America and Russia, by India and Japan. But China always swallows up the barbarians and rises again, triumphant over all. Don't you forget that." Father tapped Tzu's temples. "The hope of China is in there."

"In my head?"

"To do what Yuan Shikai did, you must first become a great general. That's why you have that monitor on the back of your neck."

Tzu touched the little black box. "Do great generals all have these?"

"You are being watched. This monitor will protect you and keep you safe. I made sure you had the perfect mama to make you very, very smart. Someday they'll give you tests. They'll see that the blood of Yuan Shikai runs true in your veins."

"Where's Mama?" asked Tzu, who at that age had no idea of what 'tests' were or why someone else's blood would be in his veins.

"She's at the university, of course, doing all the smart things she does. Your mother is one of the reasons that our city of Nanyang and our province of Henan are now leaders in Chinese manufacturing."

Tzu had heard of manufacturing. "Does she make cars?"

"Your mother invented the process that allows almost half of the light of the sun to be converted directly to electricity. That's why the air in Nanyang is always clean and our cars sell better than any others in the world."

"Then Mama should be emperor!" said Tzu.

"But your father is very important, too," said Father. "Because I worked hard when I was young, and I made a lot of money, and I used that money to pay for her research when nobody else thought it would lead to anything."

"Then you be emperor," said Tzu.

"I am one of the richest men in China," said Father, "certainly the richest in Henan province. But being rich is not enough to be emperor. Neither is being smart. Though from your mother and me, you will grow up to be both."

"What does it take to be emperor?"

"You must crush all your enemies and win the love and obedience of the people."

Tzu made a fist with his hand, as tight and strong a fist as he could. "I can crush bugs," he said. "I crushed a beetle once."

"You're very strong," said Father. "I'm proud of you all the time."

Tzu got to his feet and went around the garden looking for things to crush. He tried a stone, but it wasn't crushable. He broke a twig, but when he tried to crush the pieces, it hurt his hand. He crushed a worm and it made his hands smeary with ichor. The worm was dead. What good was a crushed worm? What was an enemy? Would it look like this when he crushed one?

He hoped his enemies were softer than stone. He couldn't crush stones at all. But it was messy and unpleasant to crush worms, too. It was much more fun to let them crawl across his hand.

Tutors began to come to the house. None of them played with him for very long at a time, and each one had his own kind of games. Some of them were fun, and Tzu was very good at many of them. Children were also brought to him, boys who liked to wrestle and race, girls who wanted to play with dolls and dress up in adult clothing. "I don't like to play with girls so much," said Tzu to his father, but Father only answered, "You must know all kinds of people when you rule over them someday. Girls will show you what to care about. Boys will show you how to win."

So Tzu learned he should care about tending babies and bringing home things for the pretend mama to cook, though his own mama never cooked. He also learned to run as fast as he could and to wrestle hard and cleverly and never give up.

When he was five years old, he read and did his numbers far better than the average for his age, and his tutors were well-satisfied with his progress. Each of them told him so.

Then one day he had a new tutor. This tutor seemed to be more important than all the others. Tzu played with him five or six times a day, fifteen minutes at a time. And the games were new ones. There would be shapes. He would be given a red one that was eight small blocks stuck together, and then from a group of pictures of blocks he had to choose which one was the same shape. "Not the same color -- it can be a different color. The same shape," said the tutor.

Soon Tzu was very good at finding that shape no matter how the picture was turned around and twisted, and no matter what color it was. Then the tutor would bring out a new shape, and they'd start over.

He was also given logic questions that made him think for a long time, but soon he learned to find the classifications that were being used. All dogs have four legs. This animal has four legs. Is it a dog? Maybe. Only mammals have fur. This animal has fur. Is it a mammal? Yes. All dogs have four legs. This animal has three legs. Is it a dog? It might be an injured dog -- some injured dogs have only three legs. But I said all dogs have four legs. And I said some dogs have only three legs because they're broken but they're still dogs! And the tutor smiled and agreed with him.

Then there were the memorization tests. He learned to memorize longer and longer lists of things by putting them inside a toy cupboard the tutor told him to create in his mind, or by mentally stacking them on top of each other, or putting them inside each other. This was fun for a while, though pretty soon he got sick of having all kinds of meaningless lists perfectly memorized. It wasn't funny after a while to have the ball come out of the fish which came out of the tree which came out of the car which came out of the briefcase, but he couldn't get it out of his memory.

Once he had played them often enough, Tzu became bored with all the games. That was when he realized that they were not games at all. "But you must go on," the tutor would say. "Your father wants you to."

"He didn't say so."

"He told me. That's why he brought me here. So you would become very good at these games."

"I am very good at them."

"But we want you to be the best."

"Who is better? You?"

"I'm an adult."

"How can I be best if nobody is worst?"

"We want you to be one of the best of all the five-year-old children in the world."

"Why?"

The tutor paused, considering. Tzu knew that this meant he would probably tell a lie. "There are people who go around playing these games with children, and they give a prize to the best ones."

"What's the prize?" asked Tzu suspiciously.

"What do you want it to be?" asked the tutor playfully. Tzu hated it when he acted playful.

"Mama to be home more. She never plays with me."

"Your mama is very busy. And that can't be the prize because the people who give the prize aren't your mama."

"That's what I want."

"What if the prize was a ride in a spaceship?" said the tutor.

"I don't care about a ride in a spaceship," said Tzu. "I saw the pictures. It's just more stars out there, the same as you see from here in Nanyang. Only Earth is little and far away. I don't want to be far away."

"Don't worry," said the tutor. "The prize will make you very happy and it will make your father very proud."

"If I win," said Tzu. He thought of the times that other children beat him in races and wrestling. He usually won but not always. He tried to think how they would turn these games into a contest. Would he have to make shapes for the other child to guess, and the child would make shapes for him? He tried to think up logic questions and lists to memorize. Lists that you couldn't put inside each other or stack up. Except that he could always imagine something going inside something else. He could imagine anything. He just ended up with more stupid lists he couldn't forget.

Life was getting dull. He wanted to go outside of the garden walls and walk around the noisy streets. He could hear cars and people and bicycles on the other side of the gate, and when he stuck his eye right up against the crack in the gate he could see them whiz by on the street. Most of the pedestrians were talking Chinese, like the servants, instead of Common, like Father and the tutors, but he understood both languages very well, and Father was proud of that, too. "Chinese is the language of Emperors," said Father, "but Common is the language that the rest of the world understands. You will be fluent in both."

But even though Tzu knew Chinese, he could hardly understand what was said by the passersby. They spoke so quickly and their voices rose and fell in pitch, so it was hard to hear, and they were talking about things he didn't understand. There was a whole world he knew nothing about and he never got to see it because he was always inside the garden playing with tutors.

"Let's go outside the walls today," he said to his Common tutor.

"But I'm here for us to read together," she said.

"Let's go outside the walls and read today," said Tzu.

"I can't," she said. "I don't have the key."

"Mu-ren has a key," said Tzu. He had seen the cook go out of the gate to shop for food in the market and come back with a cart. "Pei-Tian has a key, too." That was Father's driver, who brought the car in and out through the gate.

"But I don't have a key."

Was she really this stupid? Tzu ran to Mu-ren and said, "Wei Dun-nuan needs a key to the gate."

"She does?" said Mu-ren. "Whatever for."

"So we can go outside and read."

By then Mu-ren had caught up with him. She shook her head at Mu-ren. Mu-ren squatted in front of Tzu. "Little master," she said, "you don't need to go outside. Your papa doesn't want you out on the street."

That was when Tzu realized he was a prisoner.

They come here and teach me what Father wants me to learn. I'm supposed to become the best child. Even the children that come here are the ones they pick for me. How do I know if I'm the best, when I never get to find children on my own? And what does it matter if I'm best at boring games? Why can't I ever leave this house and garden?

"To keep you safe," Father explained that evening. Mu-ren or the tutor must have told him about the key. "You're a very important little boy. I don't want you to be hurt."

"I won't be hurt."

"That's because you won't go out there until you're ready," said Father. "Right now you have more important things to do. Our garden is very large. You can explore anywhere you want."

"I've looked at all of it."

"Look again," said Father. "There's always more to find."

"I don't want to be the best child," said Tzu. "I want to see what's outside the gate."

"After you take the tests," said Father, laughing. "Plenty of time. You're still very very young. Your life isn't over yet."

The tests. He had to take the tests first. He had to be best child before he could go out of the garden.

So he worked hard at his games with the tutors, trying to get better and better so he could win the tests and go outside. Meanwhile, he also studied all the walls of the garden to see if there was a way to get through or under or over them without waiting.

Once he thought he found a place where he could squeeze under a fence, but he no sooner had his arm through than one of the tutors found him and dragged him back in. The next time that place had tight metal mesh between the bottom of the fence and the ground.

Another time he tried to climb a box set on top of a bin, and when he got to the top he could see the street, and it was glorious, hundreds of people moving in all directions but almost never bumping into each other, the bicycles zipping along and not falling over, and the silent cars crawling through as people moved out of the way for them. Everyone wore bright colors and looked happy or at least interested. Every single person had more freedom than Tzu did.

What kind of emperor will I be if I let people keep me inside a cage like a pet bird?

So he tried to swing his leg up onto the top of the wall, but once again, before he could even get his body weight onto the top, along came a tutor, all in a dither, to drag him down and scold him. And when he came back to the place, the bin was no longer near the wall. Nothing was ever near the garden walls again.

Hurry up with the tests, then, thought Tzu. I want to be out there with all the people. There were children out there, some of them holding onto their mothers' hands, but some of them not holding onto anybody. Just ... loose. I want to be loose.

Then one day the newest tutor, Shen Guo-rong, the one with the logic games and lists, stood outside Tzu's room and talked with his father in a low voice for a long time. He came in with a paper, which he looked at long and hard.

"What's on that paper?"

"A note from your father."

"Can I read it?" asked Tzu.

"It's not a note to you, it's a note to me," said Guo-rong.

But when he set it down, it wasn't a note at all. It was covered with diagrams and words. And that day, all their games were chosen by Guo-rong after consulting with the paper.

It went like that for days. Always the same answers, until Tzu knew them all in order and could start reciting them before the questions were asked.

"No," said Guo-rong. "You must always wait for the question to be completely finished before you answer."

"Why?"

"That's the rule of the game," he said. "If you answer any question too fast, then the whole game is over and you lose."

That was a stupid rule, but Tzu obeyed it. "This is boring," he said.

"The test will be soon," said Guo-rong. "And you'll be completely ready for it. But don't tell the testers about any of your practice with me."

"Why not?"

"It will look better for you if they don't know about me, that's all."

That was the first time that Tzu realized that there might be something wrong with the way he was being prepared for the tests. But he had little time to think about it, because the very next day, a strange woman and a strange man came to the house. They had no folds over their eyes and had strange ruddy skin, and they wore uniforms he recognized from the vids. They were with the I.F., the International Fleet.

"He's fluent in Common?" the man said.

"Yes," said Father -- Father was home! Tzu ran into the room and hugged his father. "This is a special day," Father told him as he hugged him back. "These people are going to play some games with you. A kind of test."

Tzu turned and looked at them. He didn't know the test was from soldiers. But now it became clear to him. Father wanted him to become a great general like Yuan Shikai. The beginning of that would be to enter the military. Not the Chinese Army, but the fleet of the whole world.

But he didn't want to go into space. He just wanted to go out on the street.

He knew Father would not want him to ask about this, however. So he smiled at the man and the woman and bowed to each in turn. They bowed back, smiling also.

Soon Tzu was alone in his playroom with the two of them. No tutors, no servants, no Father.

The woman spread out some papers and brought out shapes, just like the ones he had practiced with.

"Have you seen these before?" she asked.

He nodded.

"Where?"

Then he remembered he wasn't supposed to talk about Guo-Rong, so he just shrugged.

"You don't remember?"

He shrugged again.

She explained the game to him -- it was just like the one Guo-Rong had played. And when she held up a shape, it was the very one they had practiced with, and he instantly recognized it from the choices on the paper. He pointed.

"Good," she said.

And so it went with the next two shapes. They were exactly the ones Guo-rong had shown him, and the answer was exactly the one that had been on the note from Father.

Suddenly Tzu understood it all. Father had cheated. Father had found out the answers to the test and had given them to Guo-rong so that Tzu would know all the answers to all the questions.

It took only a moment to make the next leap. In a way, it was a logic problem. The best child is the one who scores the best on this test. He wants me to be best child. So I must score the best on this test.

But if I score the best because I was given the answers in advance and trained to memorize them, then this test won't prove I'm the best child, it will only prove that I can memorize answers.

If Father believed I was best child, then he would not need to get these answers in advance. But he did get the answers. Therefore he must believe that I would not have won the test without having special help. Therefore Father does not believe I am best child, he just wants to fool other people into believing that I am.

It was all he could do to keep from crying. But even though his eyes burned and he felt a sob gathering behind his nose and in his throat, he kept his face calm. He would not let the people know that his father had given him the answers. But he would also not pretend to be best child when he really wasn't.

So the next question he got wrong.

And the next.

And all the others.

Even though he knew the answer to every single one, before they even finished the question, he got every one of them wrong.

The woman and man from the International Fleet showed no sign of whether they liked his answers or not. They smiled cheerfully all the time, and when they were done, they thanked him and left.

Afterword, Father and Guo-rong came into the room where Tzu waited for them. "How did it go?" asked Father.

"Did you know the answers?" asked Guo-rong.

"Yes," said Tzu.

"All of them?" asked Father.

"Yes," said Tzu.

"Did you answer all the questions?" asked Guo-rong.

"Yes," said Tzu.

"Then you did very well," said Father. "I'm proud of you."

You're not proud of me, thought Tzu as his father hugged him. You didn't believe I'd pass the test on my own. You didn't think I was best child. Even now, you're not proud of me, you're proud of yourself for getting all the answers.

There was a special dinner that night. All the tutors ate with Father and Tzu at the main table. Father was laughing and happy. Tzu could not help but smile at all the smiling people. But he knew that he had answered all but the first three questions wrong, and Father would not be happy when he found that out.

When dinner was over, Tzu asked, "Can I go outside the gate now?"

"Tomorrow," said Father. "In daylight."

"The sun is still up," said Tzu. "Take me now, Father."

"Why not?" said Father. He rose to his feet and took Tzu by the hand and they walked, not to the gate where the car came in and out, but to the front door of the house. It let out onto another garden, and for a moment Tzu thought his father was going to try to fool him into thinking this was the outside when it was really more garden. But soon the path led to a metal gate which opened at Father's touch, and beyond the gate was a wide road with many cars on it -- more cars than people. It was a different world from what Tzu had seen over the back fence. It was so quiet. The cars glided silently by, their tires hissing on the pavement, though there were some that had no tires and merely hovered over the concrete of the road.

"Where are all the people and bicicyles?" asked Tzu.

"Behind the house is a back road," said Father. "Where poor people go about their business. This is the main road. It connects to the highway. These cars could be going anywhere. Xiangfan. Zhengzhou. Kaifeng. Even Wunan or Beijing or Shanghai. Great cities, where powerful people live. Millions of them. In the richest and greatest of all nations." Then Father picked Tzu up and held him on his hip so their faces were close. "But you are the best child in all those cities."

"No I'm not," said Tzu.

"Of course you are," said Father.

"You know that I'm not," said Tzu.

"What makes you say that?"

"If you thought I was best child, you wouldn't have given Guo-rong all the answers."

Father just looked at him for a moment. "I was just making sure. You didn't need them."

"Then why did you have him teach them to me?" said Tzu.

"To be sure."

"So you weren't sure."

"Of course I was," said Father.

But Tzu had been studying logic. "If you were sure I would know the answers on my own, then you wouldn't have to make it sure by getting the answers. But you got the answers. So you weren't sure."

Father looked a little bit upset.

"I'm sorry, Father, but it's how we play the logic game. Maybe you need to play it more."

"I am sure that you're the best child," said Father. "Don't you ever doubt it." He set Tzu down and took his hand again. They went through the gate and walked up the street.

Tzu wasn't interested in this road. There were no people here, except in cars, and they went by too fast for Tzu to hear them. There were no children. So when they came to a side street, Tzu began to pull his father that direction. "This way," he said. "Here's all the people!"

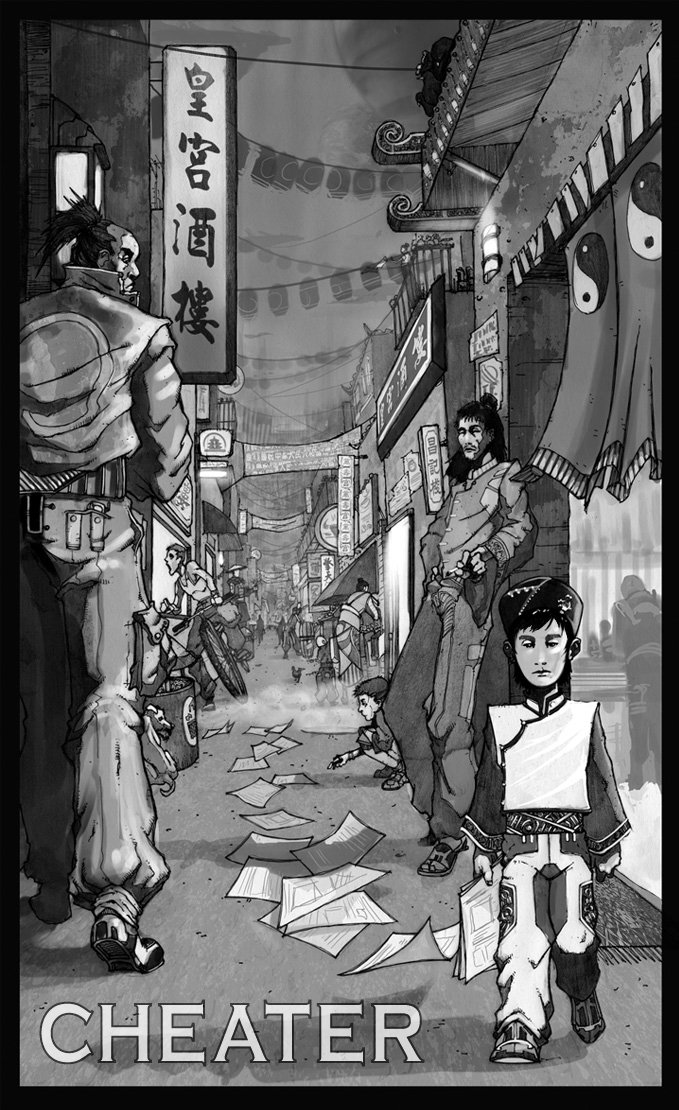

"That's why it isn't safe," said Father. But then he laughed and let Tzu lead him on into the crowds. After a while it was so jammed with people and bicycles that Father picked him up. That was much better. Tzu could see the people's faces. He could hear their conversations. Some of them looked at Tzu, being held up by his father, and smiled at them both. Tzu smiled and waved back.

Father walked slowly alongside a high fence, which Tzu realized was the back fence around their garden. Eventually came to a gate, which Tzu knew was the gate to their garden. "Don't go in yet," said Tzu.

"What?"

"This is our gate, but don't go in."

"How did you know it was our gate? You've never been on this side of it before."

"Father," said Tzo impatiently, "I'm very smart. I know this is our gate. What else could it be? We've just made a circle. Let me see more before we go in."

So they walked past the gate, and on into one of the streets that seemed to go on forever, more and more people, flowing into and out of the buildings. Starting and stopping, buying and selling, calling out and keeping still, laughing and serious-faced, talking on phones and gesturing, or listening to music and dancing as they walked.

"Is this China, Father?" asked Tzu.

"A very small part of it. There are hundreds of cities, and lots of open country, too. Farmland and mountains, forest and beaches. Seaports and manufacturing centers and highways and deserts and rice paddies and wheatfields and millions and millions and millions of people."

"Thank you," said Tzu.

"For what?"

"For letting me see China before I go off into space."

"What are you talking about?"

"The man and woman with the test, they were from the International Fleet."

"Who told you that?"

"They wore the uniforms," said Tzu impatiently. But then he realized: He hadn't passed the test. He answered the questions wrong. He wouldn't be going to space after all. "Never mind," he said. "I'm staying."

Father laughed and held him close. "Sometimes I have no idea what you're talking about, Little Master."

Tzu wondered if he should tell him that he answered the questions wrong, but he decided against it. Father was so happy. Tzu didn't want to make him angry tonight.

The next morning, Tzu was eating breakfast in the kitchen with Mu-ren when someone came to the door. The visitor did not wait for old Iron-head, as Mu-Ren and Tzu secretly called him, to fetch Father. Instead, many feet began walking briskly through the house.

The kitchen door was flung open. A soldier with a weapon in his hand stepped in and looked around. "Is Han Pei-mu here?" he asked sternly.

Mu-ren shook her head.

"What about Shen Guo-rong?"

Again, the head shake.

"Guo-rong doesn't come till later," said Tzu.

"You two stay right here in the kitchen, please," said the soldier. He continued to stand in the doorway. "Keep eating, please."

Tzu continued eating, trying to think what the soldiers were there for. Mu-ren's hands were shaking. "Are you cold?" asked Tzu. "Or are you scared?"

Mu-ren only shook her head and kept eating.

After a while he could hear his father shouting. "Let me at least explain to the boy!" he was saying. "Let me see my son!"

Tzu got up from his mat on the floor and jogged toward the kitchen door. The soldier put his hand on his shoulder to stop him.

Tzu slapped his hand and said to him fiercely, "Don't touch me!" Then he jogged on down the hallway to Father's room, the soldier right behind him.

The door opened just before Tzu got to it, and there was the man from the test yesterday. "Apparently someone already decided," said the man. He ushered Tzu into the room.

Father's hands were bound together behind his back, but now one of the soldiers loosed them and he reached out to Tzu. Tzu ran to him and hugged him. "Are you under arrest?" asked Tzu. He had seen arrests on the vids.

"Yes," said Father.

"Is it because of the answers?" asked Tzu. It was the only thing he could think of that his father had ever done wrong.

"Yes," said Father.

Tzu pulled away from him and faced the man from the tests. "But it was all right," said Tzu. "I didn't use those answers."

"I know you didn't," said the man.

"What?" said Father.

Tzu turned around to face him. "I didn't like it that you were only going to pretend I was best child. So I didn't use any of the answers. I didn't want to be called best child if I wasn't really." He turned back to the man from the fleet. "Why are you arresting him when I didn't use the answers?"

The man smiled confidently. "It doesn't matter whether you used them or not. What matters is that he obtained them."

"I'm sorry," said Father. "But if my son did not answer the questions correctly, how can you prove that any cheating took place?"

"For one thing, we've been recording this entire interview," said the man from the fleet. "The fact that he knew he had been given the right answers and chose to answer incorrectly does not change the fact that you trained him to take the test."

"Maybe what you need is a little better security with the answers," said Father angrily.

"Sir," said the man from the fleet, "we always allow people to buy the test if they try to get it. Then we watch and see what they do with it. A child as bright as this one could not possibly have answered every question wrong unless he absolutely had the entire test down cold."

"I got the first three right," said Tzu.

"Yes, all but three were wrong," said the man from the fleet. "Even children of very limited intellect get some of them right by random chance."

Father's demeanor changed again. "The blame is entirely mine," he said. "The boy's mother had no idea I was doing this."

"We're quite aware of that. She will not be bothered, except of course to inform her. The penalty is not severe, sir, but you will certainly be convicted and serve the days in prison. The fleet makes no exceptions for anyone. We need to make a public example of those who try to cheat."

"Why, if you let them cheat whenever they want?" said Father bitterly.

"If we didn't let people buy the answers, they might figure out much cleverer ways to cheat the test. Ways we wouldn't necessarily catch."

"Aren't you smart."

Father was being sarcastic, but Tzu thought they were smart. He wished he had thought of that.

"Father," said Tzu. "I'm sorry about Yuan Shikai."

Father glanced furtively toward the soldiers. "Don't worry about that," he said.

"But I was thinking. It's been so many hundred years since Yuan Shikai lived that he must have hundreds of descendants now. Maybe thousands. It doesn't have to be me, does it? It could be one of them."

"Only you," said Father softly. He kissed him good-bye. They bound his wrists behind his back and led him out of the house.

The woman from the test stayed with Tzu and kept him from following to watch them take Father away. "Where will they take him?" asked Tzu.

"Not far," said the woman. "He won't be imprisoned for very long, and he'll be quite comfortable there."

"But he'll be ashamed," said Tzu.

"For a man with so much pride in his family," said the woman, "that is the harshest penalty."

"I should have answered most of the questions right," said Tzu. "It's my fault."

"It's not your fault," said the woman. "You're only a child."

"I'm almost six," said Tzu.

"Besides," said the woman, "we watched Guo-rong coaching you. Teaching you the test."

"How?" asked Tzu.

She tapped the little monitor on the back of his neck.

"Father said that was just to keep me safe. To make sure my heart was beating and I didn't get lost."

"Everything your eyes see," said the woman, "we see. Everything you hear, we hear."

"You lied, then," said Tzu. "You cheated too."

"Yes," said the woman. "But we're fighting a war. We're allowed to."

"It must have been boring, watching everything I see. I never get to see anything."

"Until last night," she said.

He nodded.

"So many people on the streets," she said. "More than you can count."

"I didn't try to count them," said Tzu. "They were going all different directions and in and out of buildings and up and down the side streets. I stopped after three thousand."

"You counted three thousand?"

"I'm always counting," said Tzu. "I mean my counter is."

"Your counter?"

"In my head. It counts everything and tells me the number when I need it."

"Ah," she said. She took his hand. "Let's go back to your room and take another test."

"Why?"

"This test you don't know the answers to."

"I bet I do," said Tzu. "I bet I figure them out."

"Ah," said the woman. "A different kind of pride."

Tzu sat down and waited for her to set up the test.

on the art and business of science fiction writing.

Over five hours of insight and advice.

Recorded live at Uncle Orson's Writing Class in Greensboro, NC.

Available exclusively at OSCStorycraft.com

We hope you will enjoy the wonderful writers and artists who contributed to IGMS during its 14-year run.